All aboard!

Winnipeg Railway Museum can punch your ticket to the past, but it also needs your help

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/08/2021 (1653 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Once packed full of perishables on their way to new markets, these days an old refrigerator train car serves to preserve memories instead.

“What it is in essence is a giant Coleman cooler on wheels. It made it possible to eat Georgia peaches in Winnipeg,” explains Gary Stempnick, president of the Midwestern Rail Association of the former role of this century-old box car, known as a reefer.

“It revolutionized the North American diet.”

Instead of food kept cool by huge ice blocks, the reefer car now houses railroading archives at the Winnipeg Railway Museum, run by the Midwestern Rail Association and the Winnipeg Model Railway Club.

“We have three and one is going up for sale,” Stempnick says, referring to the three refrigerated cars owned by the volunteer-run museum on rails.

Established more than four decades ago, the Winnipeg Railway Museum has operated from a large, rented rail shed at Platforms 1 and 2 at the Via Rail Station for the last 25 years or so. Assorted railway cars and locomotives sit on the two tracks closest to Main Street, while train-related artifacts are on display on two long sides of the museum.

“It’s the coolest indoor museum in Canada in the winter and the hottest ticket in town in summer,” quips board member Gord Leathers of the varying temperatures inside the unheated and uninsulated train shed.

The location has some ups and downs, since it catches the attention of visitors to The Forks but presents barriers to anyone not able to climb stairs.

A combination of public health measures to restrict the transmission of COVID-19 and work on the train shed walls kept the doors closed for most of the last 18 months. The not-for-profit museum relies on admission fees, donations and sales from its railway car gift shop to meet its modest annual budget of about $30,000.

“We are trying to find backers and find new ways to raise funds,” Stempnick says, explaining how his board plans to keep the museum open and operational.

Logistics aside, Stempnick and his small but dedicated crew of volunteers are keen on sharing the story of how trains built Winnipeg and Western Canada, beginning with the Countess of Dufferin, the first steam engine to puff her way across the Canadian prairies. Arriving here in 1877, the Countess served as a contractor’s locomotive, and her sturdy construction allowed her to navigate the newly built track on the Prairies.

“That’s why she was run here — because she was bringing the rail,” Stempnick says. The locomotive was originally barged up the Red River to Winnipeg. The steam engine returned to Winnipeg in 1910 and was displayed for many years in front of the Royal Alexandra Hotel at Higgins and Main.

Most of the museum’s large artifacts were donated by rail companies after being taken out of service and are no longer operational, but still fit into the museum’s mandate of explaining the past and current impact of railway on Winnipeg and Western Canada.

“It’s the history of the railroad and much of the equipment is original,” Stempnick says.

“It’s our history and the only way young people will know it’s our history is if we show them.”

Some of that history looms large in railways cars and locomotives visitors can climb into. Other stories stay out of sight, hidden in filing cabinets, bookcases and storage boxes inside the cold storage car. Volunteers plan to install a glass door so visitors can see what’s inside, but most of the archives remains off limits to the public, Stempnick says.

“We’ve had requests from various historians to come and look at stuff, but we will not let anything leave the building,” he says, adding they plan to install a worktable near the reefer car for researchers.

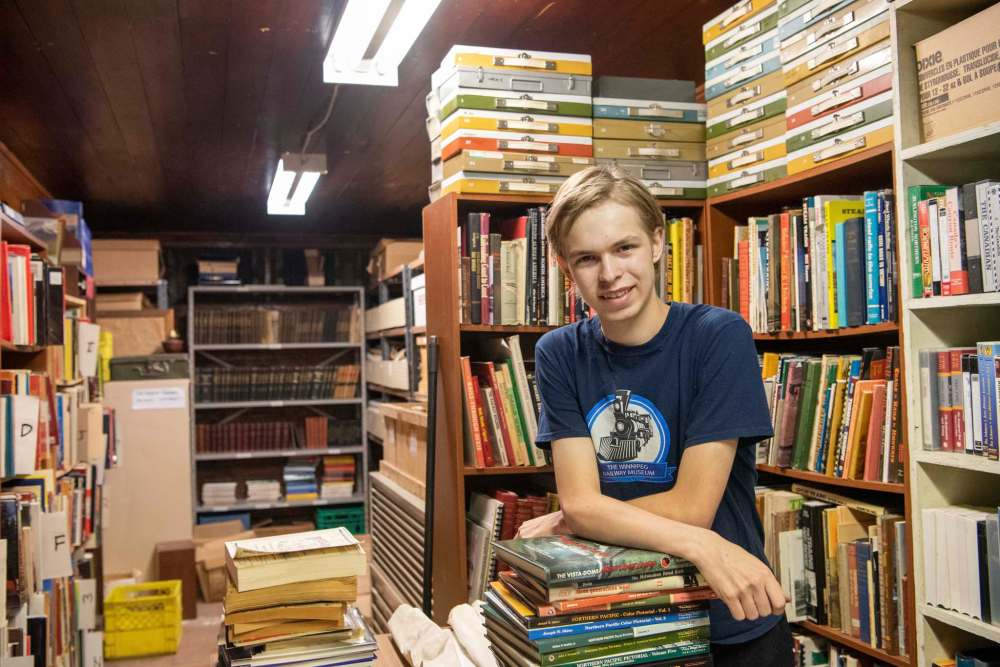

Now stuffed with boxes of town site plans, maps, surveys, timetables and government reports, the archive remains unexplored. Volunteer archivist William Yachison, a recent high school graduate, is attempting to bring some order to the decades of files, and the museum has a database of their records available for researchers.

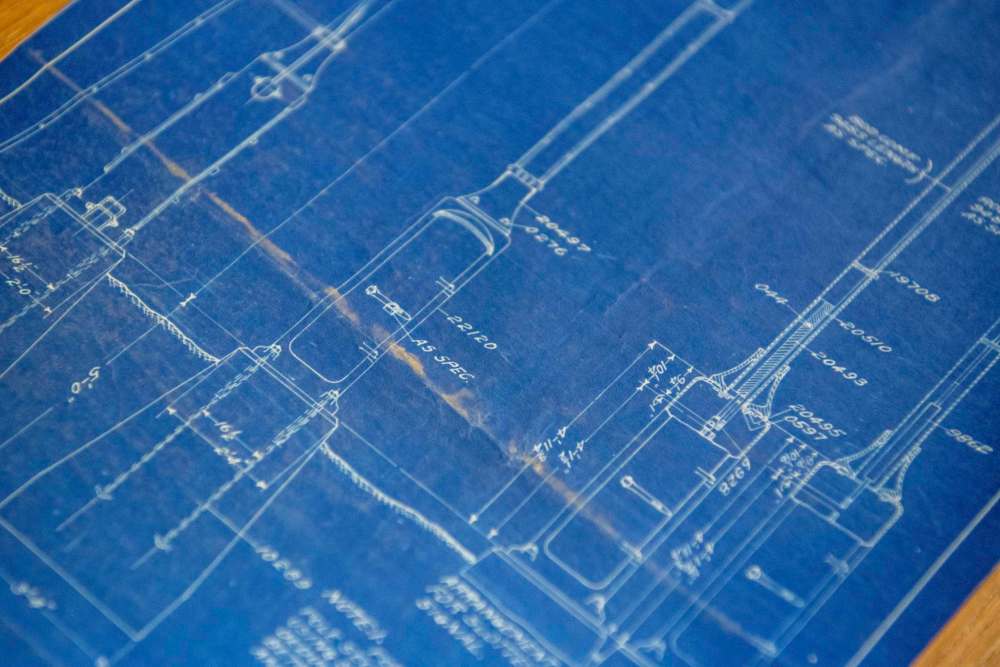

Packed with train history, from handbooks on diesel engines to detailed train schedules from every North American station, the archives also include rolls of blueprints once used by railway companies to build their network of rails.

“It’s a general diagram of how an old-school semaphore signal worked,” Yachison says, referring to a randomly chosen blueprint in the archives dated Sept. 11, 1907.

Sharp-eyed visitors strolling the long cement apron on either side of the dual tracks may also spot some quirky items amid the larger artifacts. An engine bell off the Royal Train that carried King George VI and Queen Elizabeth across Canada in the spring of 1939 is now on display, finding its way to the museum after being donated by Canadian Pacific Railway to Knox Presbyterian Church in Stonewall in 1962. A model of the same CPR steam locomotive that pulled the Royal Train sits close by, along with the newspaper article explaining that Joe Baron of Alfred Avenue spent 15 years constructing it.

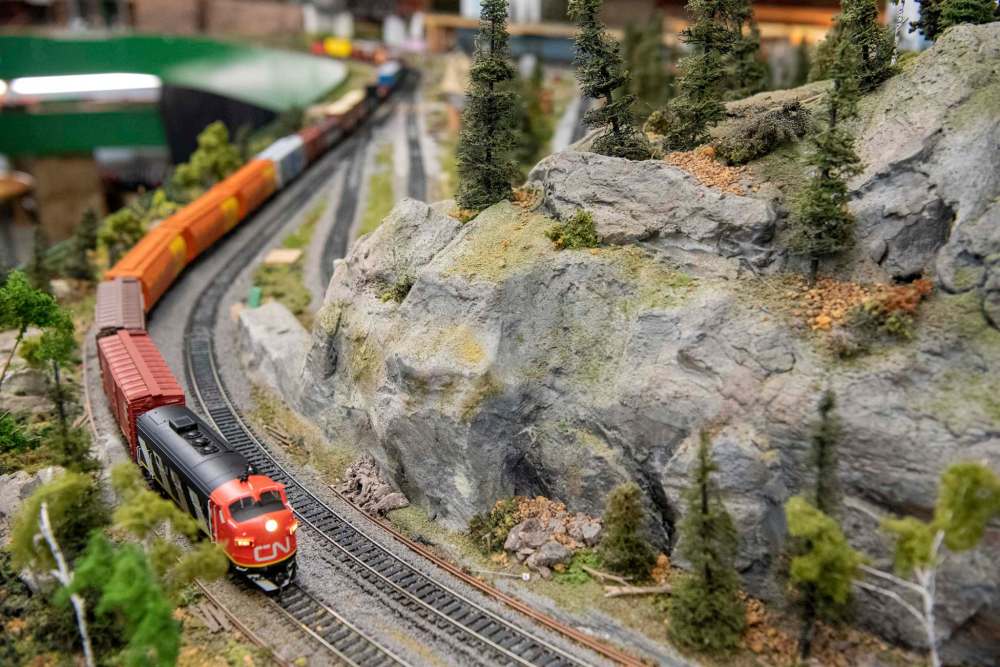

A large glass display case on the east side of the tracks houses all the scale model buildings made by the late Jock Oliphant, Canada’s first Master Model Railroader, speaking to the hours spent by hobbyists to get all the details exactly right.

“Everything is scaled but built from scratch,” Stempnick says. The Oliphant collection is located near a large room filled with working layouts of the Winnipeg Model Railway Club.

Recent acquisitions from other small museums wait to be catalogued and displayed, now shoved into roped off sections since the museum has no formal storage areas.

That type of work takes both financial resources and people power, both which are in short supply these days, admits Stempnick.

“Unless we get help, we don’t know how long we can handle this,” he says, speaking to the need for more involvement from railway and grain companies in supporting the museum.

Community museums across the province feel the same pressures and some may have to make difficult decisions to pair up with other museums or disperse their artifacts and close, says Monique Brandt of the Association of Manitoba Museums.

Others may need to play up what they have and convince the public they have artifacts worth seeing, she says.

“I look at some of the collections we have in Manitoba and Canada and these museums have the potential to be just as good,” says Brandt, adding the Countess of Dufferin would have interest to an audience well beyond Winnipeg.

Stempnick agrees the steam engine, nearing its 150th birthday, may help keep the museum on track. Volunteers plan to restore an original wooden conductor’s car, now covered in peeling yellow paint, in order to couple it to the historic steam engine, also known as CPR No. 1, to show their visitors the railway technology of the late 18th century.

“She’s big-boned, she’s tough and she’s robust,” he says.

“Without the Countess of Dufferin, that railroad may never have happened.”

brenda.suderman@freepress.mb.ca

Brenda Suderman has been a columnist in the Saturday paper since 2000, first writing about family entertainment, and about faith and religion since 2006.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.