Lessons through time Iron lung among a large collection of artifacts at the Manitoba Museum that are both a window to the past, and a warning for today

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/11/2021 (1550 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In this last installment of six-month series of visiting the backrooms and attics of Winnipeg’s museums, writer Brenda Suderman and photographer Jessica Lee tour some of the vaults at the Manitoba Museum to get a sense of the scope of the nearly three million items in their collection. In addition to the main floor public galleries, the museum boasts about 2,090 square metres (22,500 sq. ft.) of climate-controlled vaults in the six-storey tower at 190 Rupert Ave. The museum is open 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday to Sunday. Admission is $15 for adults, $13 for seniors, $9 for children and youth, and free for children two and under.

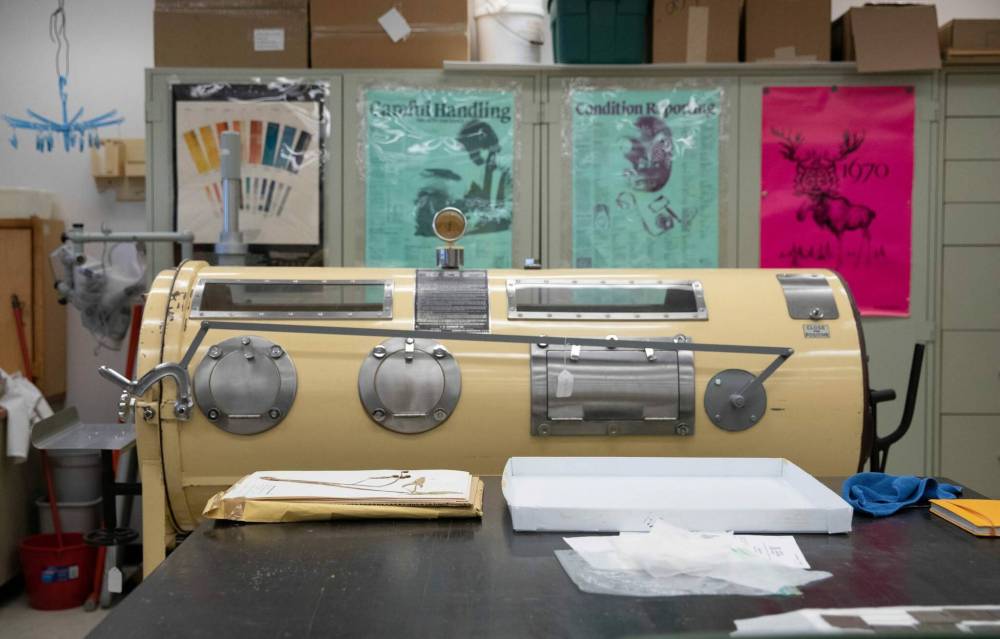

Large enough to accommodate an adult, the yellow metal cylinder in a sixth-floor museum conservation lab serves as both as an artifact of the past and a cautionary tale for the present.

“To me it speaks very much to what can happen when vaccines aren’t available and the lifelong effects of (polio),” says history curator Roland Sawatzky of the iron lungs once used by people afflicted by polio.

Donated by a rural Manitoba man who slept it in nightly to assist his breathing, the yellow metal tube on wheels features a stainless steel head rest, interior foot controls, rectangular windows, and several portholes allowing outside access.

Although it bears witness to the effects of a viral disease, largely eradicated after polio vaccines became available in 1955, the iron lung has remained in storage since the museum acquired it from its original owner 13 years ago, and will likely stay there, says Cindy Colford, manager of collections and conservation.

“This would be a good example of something that is large and takes up a lot of space and it certainly would take a lot of space on display,” she said of the iron lung.

These electric machines served as mechanical respirators for people paralyzed by poliomyelitis, polio for short. Patients often depended on iron lungs for breathing when hospitalized during the 1953 polio epidemic, but this model, weighing 272 kilograms, was designed specifically for home use, evident by the non-medical issue floral covering on the three-inch mattress inside.

“It’s a nightmare for the claustrophobic but a lifesaver,” says Sawatzky of the confined sleeping quarters.

With 2,957,031 artifacts and specimens in the museum’s collection, finding space in the 50-year-old museum building for important but bulky items always presents a challenge, says Colford.

Recently, staff designed and built wheeled crates to house their collection of animals preserved by taxidermy in a second floor climate-controlled storage space. That modification makes it easier to move around large animals such as their three bears — a cinnamon-coloured black bear, a black-furred black bear and a grizzly — for display in the galleries or research purposes.

“The museum has acquired full-sized taxidermy specimens over the years,” Colford says of their collection of 40 animals and birds found in Manitoba and surrounding provinces.

“Obviously we can’t show them all in the gallery, so we have to have a safe space for them.”

Large animals such as elk, deer and bison are housed in crates and swathed in plastic or bubble wrap, while smaller specimens such as foxes and owls sit on shelves.

Across the hall, a storage room is filled with shelves of plaster-covered fossils, many recovered decades ago on museum-sponsored digs to Horseshoe Canyon, near Drumheller, Alta., says Graham Young, curator of geology and paleontology.

“We’re looking at dinosaur parts and (this) a big package that has not been opened, even though it came in (to the museum) in 1992,” says Young of a fossil containing the pelvis and vertebrae of a duck-billed dinosaur.

With the bones disrupted during the collection process, Young says this fossil is probably not a good sample for display but could be valuable in the future for research purposes.

“It’s worth your while to collect more than you can use,” he says of the many shelves of fossils.

Last summer, the museum acquired a good quality bison skull, discovered in the banks of the Assiniboine River near Portage la Prairie. After getting it dated and determining the species of bison, Young says the museum will use it for research purposes, and the public may never see it on display.

“We’re a library of nature objects for people to study, just like they study books and texts,” he says of how their collection is available to researchers.

Ditto for the boxes and boxes of mammoth teeth and jaw bones, stored in a large vault with climate controlled conditions of 50 per cent humidity and temperatures hovering between 18 and 20 C.

“If someone offers you a good piece of a mammoth, and you’re a museum, you take it,” Young jokes about how the museum acquired several specimens of the now-extinct tusked mammal, related to living Asian elephants.

Mammoths formed their teeth in layers, with the flat sides of the molars used for grinding plant materials, similar to how a millstone would grind grain, says Young, who has worked at the museum for nearly three decades.

Likely dating between 50,000 and 100,000 years old, some of the mammoth specimens have little information attached to where or when they were collected, says Young. Some mammoth parts and other fossils were once stored in the basement of the either the Manitoba legislature or the former Winnipeg Civic Auditorium, now the Archives of Manitoba, well before the establishment of the current Manitoba Museum and the completion of its building on Rupert Avenue in 1970.

“The older the collection, the less data there is,” says Young.

Data isn’t the only thing sometimes in short supply at the province’s historical depository. Despite the nearly three million artifacts and specimens — many of them small fossils or geological samples — housed in storage rooms and vaults, museum curators remain on the hunt for specific items to fill holes in their collection. Those don’t have to be the special pieces handed down over the generations, but the everyday objects and clothing used by ordinary Manitobans in their daily lives, says Colford.

So instead of offering up grandma’s wedding dress or a baptismal gown used by generations of babies, she encourages Manitobans to dig deep into their back closets for the everyday and ordinary, such as jackets, overalls, uniforms and boots worn by working people.

“People only save things they think are pristine. We don’t have a lot of work clothes,” she says about the gaps in their collection of Manitoba’s history.

“What we really want to collect is the stinky barn clothes.”

The museum also wants all citizens to feel represented in the galleries and collections, says new chief executive officer Dorota Blumczynska, who took on the position in May.

“In my own personal journey of finding belonging in a new city, you do look for things that celebrate your story and validate your existence,” explains the Polish-born CEO, who moved to Winnipeg in 1989 as a young child.

The museum already tells the account of waves of immigration to the province and Blumczynska hopes to continue telling the stories of more recent newcomers, so they can see their traditions and culture reflected in the museum. In turn, institutions such as museums need to strengthen relationships with new Canadians to understand and celebrate their stories, she says.

“These objects will outlive us,” she says of items immigrants take with them from their countries of origin.

“There is great justice in being able to collect ordinary objects of a person’s extraordinary life.”

brenda.suderman@freepress.mb.ca

Brenda Suderman has been a columnist in the Saturday paper since 2000, first writing about family entertainment, and about faith and religion since 2006.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, November 29, 2021 10:44 AM CST: Relates stories