The gas engine that thinks it’s a diesel

Breakthrough offers the fuel savings of diesel without the drawbacks

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/08/2014 (4067 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s a breakthrough that has eluded engine researchers for more than a century. Now, it might be as little as five years away.

Around the late 1800s, Rudolf Diesel designed an engine where the fuel ignites itself. The fuel is drawn into the cylinder, and on the next upward stroke of the piston is compressed to the point it ignites itself. It is called compression ignition. It has made the diesel engine the king of efficiency, as much as twice as efficient as some gas engines, and allowed cars such as the Volkswagen Passat to drive 1,200 kilometres on a single tank of fuel.

About 114 years later, Diesel’s engine remains a niche player thanks to expensive emissions-control technology, higher-priced fuel and a now-outdated reputation for odour and dirty smoke. The technology that supplies the fuel to the cylinders and the components that strip its exhaust of pollutants such as nitrous oxide are enormously expensive, adding more than $7,000 to the price of a VW Jetta to move from gas to diesel.

It has long occurred to researchers if you could use the diesel-engine idea but with a relatively cleaner fuel such as gasoline, you could avoid the expensive exhaust treatments and costly, high-pressure fuel-injection systems.

It’s a dream that’s been elusive. Until now.

At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Prof. Rolf Reitz and his team have created two engines: one that runs on gasoline but with the efficiency of diesel, and another that could blow even diesel engines away with its efficiency.

“It’s very exciting,” said Reitz, professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Engine Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “The internal combustion (gas) engine that’s been around for more than a century is very inefficient — it began at five per cent and in the ’90s to 2000 reached 25 to 30 per cent efficiency.”

At best, gasoline engines today only achieve half of the theoretical 60 per cent maximum efficiency possible.

Diesel engines, on the other hand, use less fuel and pressurize the inside of engine cylinders to a greater degree. That translates into greater efficiency and greater fuel economy.

Reitz’s team, along with automotive technology giant Delphi and Korean carmaker Hyundai, have developed a working model of a gasoline compression-ignition engine. It is identical to a diesel engine in terms of torque and fuel efficiency but does not require any of the expensive fuel-delivery or exhaust-treatment systems in diesel engines.

The challenge, according to both Reitz and Stuart Neill, senior research officer with the National Research Council’s energy, mining and environment portfolio in Ottawa, is getting the engine to work properly across the wide range of functions we ask of engines, from idling smoothly while stopped to performing well under acceleration and at cruising speed.

“Advances in microprocessor and sensor technology are making it feasible to more precisely control the combustion process to make this happen,” Neill wrote in an email interview. “However, it is definitely not a trivial challenge to make this strategy work over the entire range of conditions that an engine is expected to operate.

“Consumers will be extremely impressed with the results when new vehicles incorporating these advanced combustion technologies hit the showroom.”

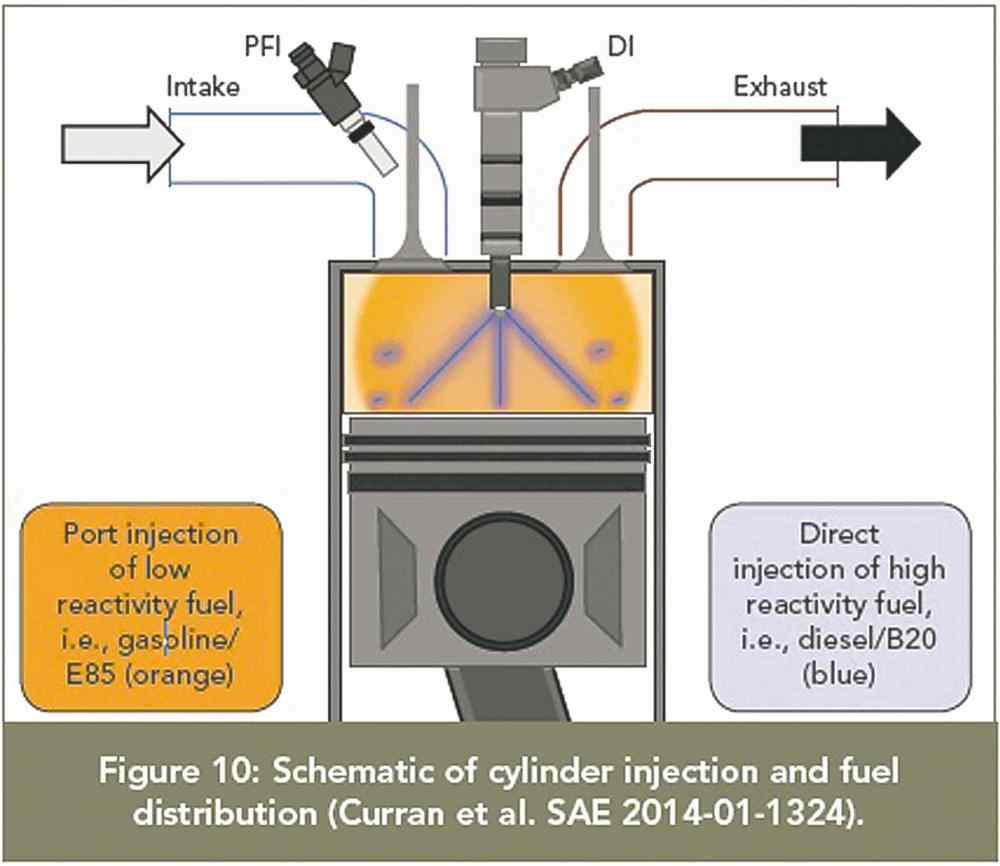

While the gasoline compression-ignition motor is promising, Reitz is even more excited about the reactivity-controlled compression-ignition motor he recently presented to the Society of Automotive Engineers’ national congress.

It has the potential to humble the diesel engine with its efficiency.

The RCCI operates like a hybrid of gasoline and diesel technology. Gasoline and air is drawn into the engine cylinder and compressed as in a regular gasoline engine, but instead of firing a spark plug at maximum compression, the RCCI engine, before the cylinder reaches maximum compression, injects some diesel fuel, which then compresses to the point of self-ignition and acts like a spark plug. The difference is, because the diesel fuel mixes with the gasoline-air mixture, it’s like an infinite number of spark plugs throughout the cylinder going off at once. That means more of the gas-air mixture ignites, resulting in better efficiency and reduced pollution.

“We’ve achieved efficiency of 59 per cent,” Reitz said, one per cent off the theoretical maximum. Reitz cautions that’s not over the entire range of engine conditions, but said it’s very promising. And, it leaves diesel engines, with their 40 per cent efficiency, eating its dust.

The RCCI engine in the university’s mock-up works much like the Chevrolet Volt or Honda Accord Hybrid, where the engine is merely driving a generator to power electric motors connected to the wheels. Reitz said the technology could boost fuel economy by as much as 20 per cent.

Reitz said more work is necessary before a gasoline compression-ignition motor or a reactivity-controlled compression ignition is ready for production, but predicted a hybrid motor — which uses compression ignition for part of the cycle and traditional spark-ignition at other times — could be as close as five years away.

kelly.taylor@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.