Books

Smartphones deeply intertwined with our personal lives

4 minute read Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025Consider for a moment the stress of misplacing your iPhone or Android device. Now compare this to 20 years ago, and how you might feel about misplacing a flip phone.

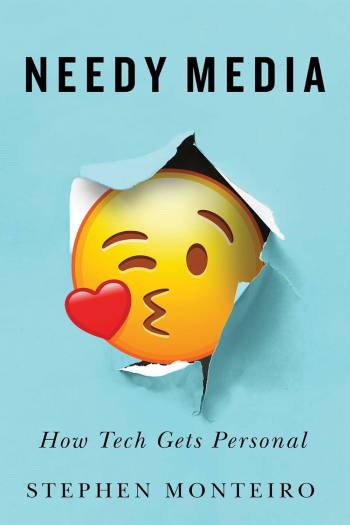

In Needy Media: How Tech Gets Personal professor Stephen Monteiro, who teaches in the department of communications at Concordia University, shows what has changed and why, illustrating how our lives are now intertwined with our personal devices. Losing one of these is much more than losing a flip phone.

Our devices now collect personal data while adjusting to our hour-by-hour activities. Like a suspicious spouse, these devices are needy; they track our activities via GPS, store our experiences through video and photos and even monitor our conversations. Depending on which apps we download, they know our musical likes and dislikes, our sleeping patterns, our calorie intake and when we exercise (or not). They also now recognize our faces and fingerprints. In other words, our personal devices have made us more “bionic” than ever before.

How did we get here? Monteiro provides a history of home computers and personal technologies. This includes hobbyists in the 1970s who purchased computer kits like the Altair 8800. These kits required a lot of effort to assemble, and often failed to work in the end. When they did function, they “computed” by the user flipping toggle switches rather than through a keyboard or mouse.

Advertisement

Weather

Winnipeg MB

-14°C, Cloudy with wind

Feline companion beguiling, insightful

4 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025Smith’s quasi-satirical gen Z characters navigate pitfalls of work, sex and alienation

5 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025Nail salon owner offers keen observations of human behaviour in Thammavongsa’s debut novel

6 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025IRA informant cover-up at the core of Herron’s latest Slow Horses thriller

5 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025Pinker ruminates on common knowledge, human interaction and more in brain-busting new tome

4 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025New Toews novel coming in 2027: literary mag report

4 minute read Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025Manitoba-born, Toronto-based Miriam Toews visited town recently in support of A Truce That Is Not Peace, her non-fiction musings on why she writes. And according to Publishers Weekly, Toews fans won’t have to wait too long for her next novel.

In a report on recent acquisitions of future books, Publishers Weekly notes that Bloomsbury, Toews’ longtime U.S. publisher, has picked up American rights for “an untitled novel by Miriam Toews, which sees a woman unpack the events leading up to her friend’s mysterious death in a religious town.” The book is slated to be published in fall 2027.

● ● ●

Winnipeg Public Library writer in residence (and Free Press copy editor) Ariel Gordon has put out the call for those looking to join a new writing circle for scribes in any genre.

Renewal of widespread human-rights commitment key

4 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025Icelandic literary legend Stefánsson making afternoon book club visit

3 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025New in paper

1 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025Familiar fodder in dystopian coming-of-age novel

3 minute read Preview Saturday, Nov. 1, 2025Thin Air director closes book on job

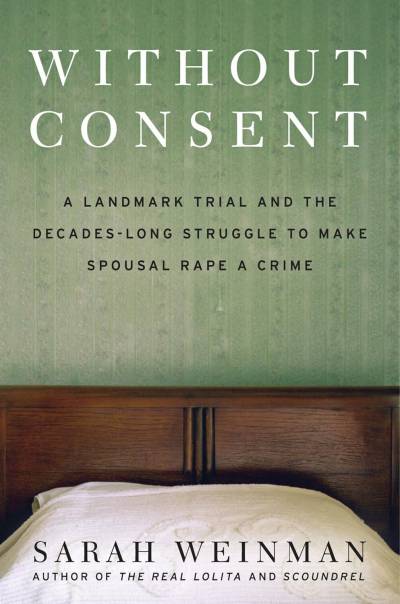

2 minute read Preview Thursday, Dec. 4, 2025Rideout spousal rape trial at the core of treatise on women’s rights and the law

4 minute read Preview Saturday, Dec. 27, 2025Winnipeg’s iconic intersection chronicled in timely, well-researched account

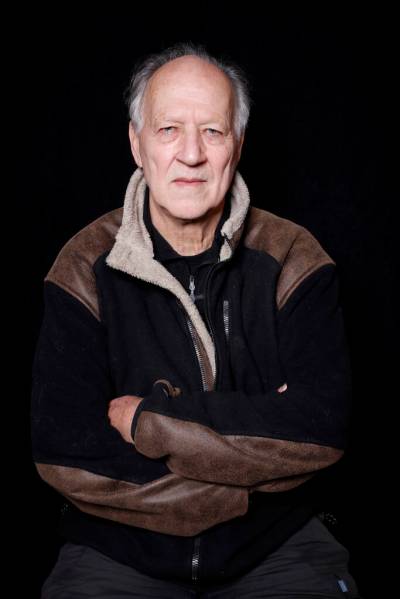

5 minute read Preview Saturday, Dec. 27, 2025Herzog ruminates on life’s truths and fictions in enchanting, philosophical prose in The Future of Truth

5 minute read Preview Saturday, Dec. 27, 2025Collection contemplates the left in deft, urgent verse

4 minute read Saturday, Dec. 27, 2025Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi’s latest collection, The Book of Interruptions (Wolsak and Wynn, 96 pages, $22), speaks to the present political and cultural moment on the left. These are, in part, documentary poetics for a dissociative, violent age, an accumulation of “horror’s lyricism/ such/ a theatrical end times.”

In the resonance of “an echo/ of a city/ that screams/ and screams/ and screams” Mohammadi uses a combination of dream- and delirium-inflected language amplified by and in tension with the material conditions of the speaker’s life: “in the city that screams/ my thoughts are taller than me/ I’m between two hemispheres/ tight-latched with worries of inflation.” The collection gathers momentum fragment on fragment, image upon image, motif on motif, to disorienting effect.

The final movement folds language and time on themselves and engages with a tradition of revolutionary messianism. Like the rest of the collection, this poem is at once disorienting, compelling, and urgent: “a foretold history where no future is an epoque (…) a word, then a word then anger. a word salad a word sandwich. a language crashing at the heat of the sun.”

● ● ●

LOAD MORE