A war without wartime mentality

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/01/2021 (1877 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

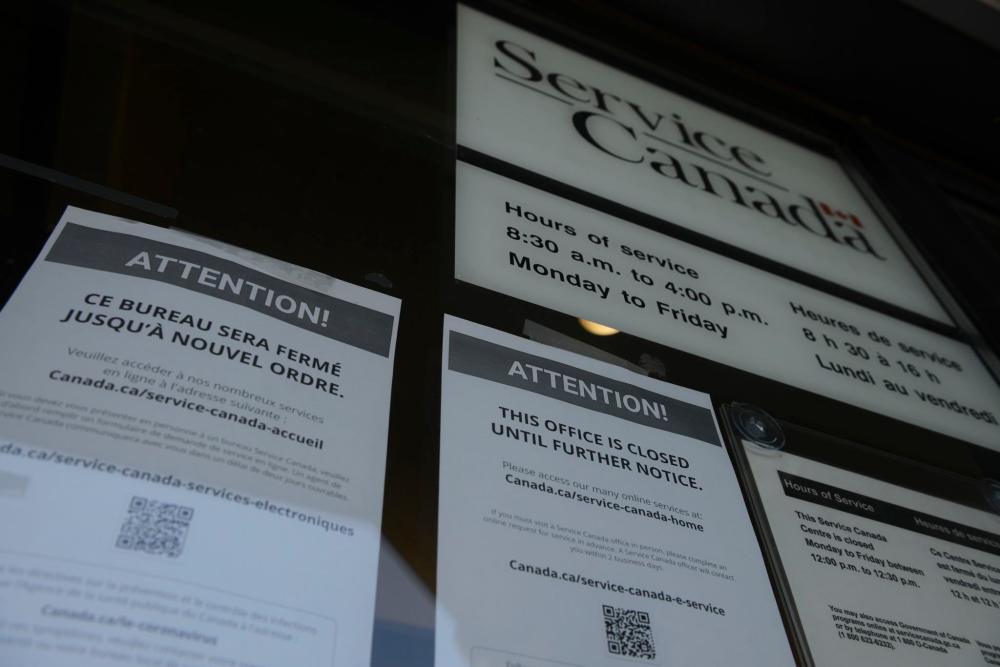

It would not be wrong to describe the global COVID-19 pandemic as a war.

Death, destruction of the social and economic fabric of society, along with the fear and dread that comes with a mortal threat. Those who have been through actual military conflict may beg to differ, but for most of the rest of us, this is war.

It begs an important question: why aren’t we using a wartime mindset to guide our response?

There has been an undeniable lack of urgency in many aspects that seems out of step with the scope and nature of the threat posed by COVID-19.

Many provinces, including Manitoba, paused vaccination programs over the Christmas holidays. There isn’t a single person working in the health-care system that doesn’t deserve a lengthy paid vacation. But given the novel coronavirus did not take any time off, it’s hard to see the virtue of suspending the vaccination effort.

A story in Monday’s Free Press by national correspondent Dylan Robertson examined internal planning documents from Health Canada’s strategic policy branch, detailing ideas and proposals made to the provinces to support the pandemic response.

Virus-fighting proposals relegated to reject pile

Posted:

OTTAWA — A month into the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadians were ready to pull out all the stops. Car manufacturers were looking into making ventilators, while thousands of citizens volunteered to help the health system.

According to the documents, the policy branch identified thousands of idle federal public servants to work as contract tracers, and tens of thousands of volunteers with experience in long-term care and medical backgrounds to support provincial health-care systems.

Although it wasn’t clear what happened after these offers were made, it does not appear many were ever acted upon. Manitoba suffered through shortages of testing and contact tracing and, by all reports, only a handful of staff from Statistics Canada were ever redeployed to support its response.

If we had employed a wartime mentality, human and non-human resources would have been rushed to the front lines. All offers of skilled volunteer support would have been taken seriously. A wartime mentality draws a direct line between the time it takes to mount a response and the number of lives that are at risk.

In this pandemic, the pace of response has been in conflict with the magnitude of the response.

A wartime mentality draws a direct line between the time it takes to mount a response and the number of lives that are at risk.

It became evident early on in the first-wave of COVID-19 Manitoba was going to need more doctors, nurses and support staff in hospitals and long-term care homes. Despite that realization, the province’s attempts to find more warm, skilled bodies stumbled badly.

Shared Health took the unusual step of surveying nurses to see who could support critical care. As it turned out, it did not know exactly how many had the critical care training. After casting about for volunteers, it quickly became evident Manitoba was desperately short of critical care bench strength and a training program was devised.

Imagine the pandemic was a fire. If we apply our current approach: rather than rushing fire trucks to the scene, we paused instead to survey city employees to see who could drive the truck and operate the pumps.

The pandemic has exposed blind spots in the health-care system that existed long prior. Across the country, the health-care system has been squeezed to control expenditures until it has lost its capacity to deal with a surge in demand for services. Canada failed to stockpile medical supplies, including personal protective equipment, and failed to provide comprehensive pandemic planning.

There have been other mistakes in strategy not explained by a lack of capacity or inattention to planning.

In late July, it became clear Winnipeg did not have enough sites or staff to conduct COVID-19 tests. Citizens were reporting intolerable waits; some found out after waiting all day in line they could not get a test at all.

What was the government’s response?

In August, weeks after the long waits manifested, the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority issued request for expressions of interest (RFEOI) to find new testing sites. However, after nearly six weeks, a WRHA spokesman confirmed there were “zero responses/expressions of interest.”

The fact no one responded to the RFEOI is not really the point. The real concern here is why the WRHA went through this process at all when it was facing a public health emergency.

Demand for more testing capacity began in July, but it took until early October to open new sites. The delay in expanding testing capacity is a major contributing factor to the deadly fall experienced in Manitoba.

We have some experience in this province responding to emergencies, but it seems the instincts we’ve developed to plan for a flood or a forest fire have been ignored during a pandemic.

We have some experience in this province responding to emergencies, but it seems the instincts we’ve developed to plan for a flood or a forest fire have been ignored during a pandemic.

Perhaps the people who draft emergency responses were excluded from pandemic planning. Or government bean counters assigned to oversee pandemic planning just wouldn’t let anyone do their job properly.

Either way, our response has lacked the urgency needed to control the spread of a deadly virus. For those of us who survive, that is something we will have to live with for a very long time.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, January 11, 2021 8:37 PM CST: Fixes minor typos