Smokehouse blues

A transformer explosion left much of Alan Ollinger's sanctuary of priceless records, instruments and collectibles charred and melted; turns out time and hard work can -- mostly -- mend a broken heart

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/10/2020 (1895 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Following a 2013 fire that charred or destroyed an exhaustive collection of records, musical instruments and assorted rock ‘n’ roll keepsakes, friends and family reached out to Alan Ollinger, telling him they were sorry for his loss.

Even a neighbour who was in the hospital battling cancer expressed sympathy that items Ollinger spent years amassing had literally gone up in smoke. That’s OK, he told everybody, always adding that at the end of the day it was “just stuff.” A few months later, however, once the initial shock had subsided somewhat, the married father of three admits to, in his words, snapping.

“One morning I woke up and yelled out, ‘Yeah, it was just stuff. But it was my stuff! And it was pretty cool stuff!’”

This is the story of Ollinger’s “stuff,” and to borrow a line from Don McLean’s American Pie, the day the music died.

● ● ●

Ollinger, born and raised in Calgary, was 12 years old in 1966 when he bought his first record, a 45 r.p.m. copy of the Herman’s Hermits chestnut, No Milk Today, using money he earned cutting lawns. He chuckles, noting his taste had improved somewhat by the time he picked up his first full-length album a year or so later, the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s debut LP, Are You Experienced.

“I had an older brother, who has sadly passed away, who bought records, too,” he continues, crediting their father, Ernie, who grew up in Sudbury and once led a jazz outfit that entertained audiences across Ontario, for turning them onto music in the first place.

“Except my brother was more into singers like Dean Martin and Bobby Darin and never seemed to mind too much when I borrowed his (Led) Zeppelin and Moody Blues albums and ‘forgot’ to give them back.”

Skip ahead some years; by the time Ollinger, a cabinet-maker by trade, and his wife Leila (“like the avenue,” he says in a rehearsed manner, when asked how to spell her name) were preparing to move to Winnipeg in 1985, he had a “crapload” of records; so many, in fact, that he had to part with a few hundred, in order to fit the rest of their possessions into a rented U-Haul.

The collecting bug bit again, mind you, after they moved into their present home, a spacious bi-level, in 1987. Soon he was spending weekends perusing second-hand shops and flea markets, replacing albums he’d sold in addition to picking up ones he hadn’t owned before. Score: while poking through boxes at a garage sale in Wolseley in the early 1990s, he bumped into someone whose kitchen he’d redesigned. When his former client asked him what he was looking for, and he replied “records,” the fellow invited him back to his place, where he had close to 1,500 titles gathering dust in the attic. “Here, take ’em all,” he said.

Earlier, we mentioned instruments. When Ollinger, who took up guitar at age 13, wasn’t filling his boots, record-wise, he was collecting guitars, mainly basses, as well as vintage amplifiers. In order to properly store his treasures, he designed and constructed a self-contained, four-season man-cave — from the outside it looks like a garage — in the backyard, steps away from a stone patio.

“Over time, it became our sanctuary,” he says of the 600-square-foot structure, which he completed in 2003. “My wife and I would invite neighbours over, open a bottle of wine and take turns choosing what records to throw on the turntable.”

● ● ●

The Ollingers were preparing to sit down for dinner on a Friday night in May 2013 when their oven went “Boom!” immediately followed by a flash of light. Hmm, that was odd, they said practically in unison. Thirty seconds later it happened again. As they eventually discovered, a transformer a block from where they live had exploded, releasing all the line voltage and sending a power surge into homes throughout the neighbourhood. Simply put, their kitchen appliances, TV, computer and various other electrical devices were toast.

Preoccupied with what occurred inside the house, it wasn’t until Sunday morning that Ollinger ventured into his backyard getaway. The first words out of his mouth when he opened the door were, “Holy f–k.” Handing over a photo he snapped that morning, he describes the scene as something out of a nightmare: the walls and ceiling were blackened, and the smell of smoke was heavy in the air. Guitars and amps were ruined, most of his records were damaged; heck, firefighters who visited that afternoon commented if Ollinger hadn’t built the space as airtight as he had, everything would have burned to the ground, and likely would have sparked fires in his and his neighbours’ homes.

“They also told me that if I had stepped through the door (on Friday night), the fire would have gotten the oxygen it needed and caused a backdraft, which would have meant we’d also have been dealing with loss of life: mine,” he says, adding the fire crew traced the cause of the blaze to a power bar that, despite being equipped with a surge protector, couldn’t handle the charge that shot through it when the transformer exploded, causing a fire that burned, in their estimation, for about an hour before going out on its own.

Later that week an insurance adjuster told Ollinger he should begin making inquiries to determine how much it would cost to replace what had been destroyed. Ollinger replied that was going to be somewhat difficult, owing to the fact many of his possessions were rare, and it wasn’t as if he could walk into Walmart to scoop up another manufacturer-signed guitar or first-edition Doors record. Or a gong.

Eventually, after moving everything to a storage facility and taking close to a year to assess what could and couldn’t be salvaged, Ollinger’s insurance company made him an agreeable offer. Afterwards, he asked them what they planned to do with the “writeoffs.” “We don’t know,” they said. “How about if I buy ‘em back from you?” he retorted. “Sure,” they said.

After tearing everything down to the studs and rebuilding his lair, adding heat sensors, fire-resistant drywall and upgraded carpeting, he went to work trying to restore his possessions. As a cabinet maker who is more than comfortable working with wood, he started with the guitars, disassembling each one, then revitalizing them from scratch, one knob, string and fretboard at a time. Next, he devised a homemade formula for cleaning smoke off record sleeves and vinyl albums. While it’s true every fifth record was so badly warped he had no choice but to toss it out, he was able to save enough that he grew more and more hopeful that, in time, he would have a collection he could be proud of again.

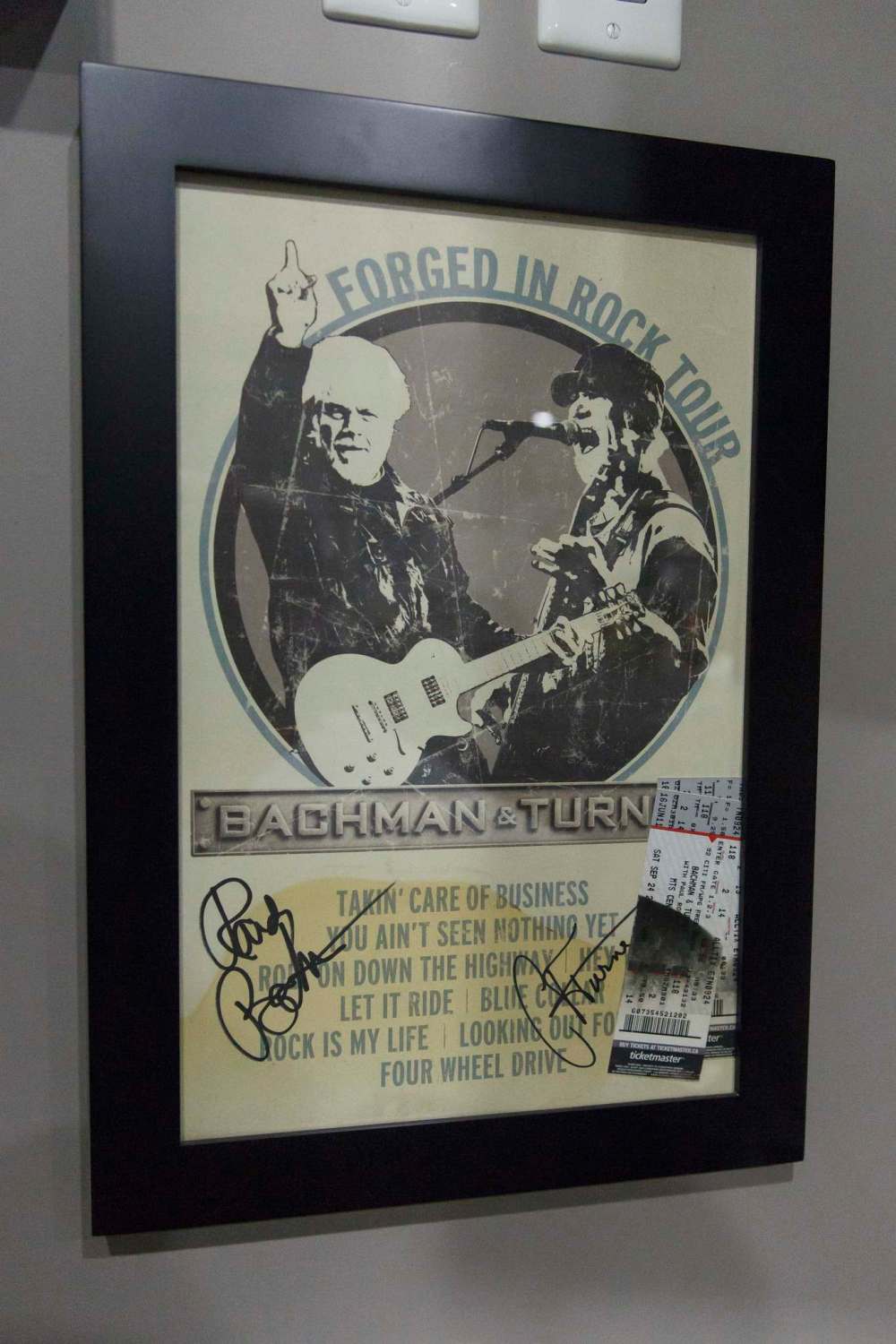

Ollinger moved back into his retreat just before Christmas 2014, about 19 months after the fire. Since then, he’s continued collecting, trading and accumulating gems so that his cache is currently at a level, numbers-wise, similar to what it was pre-accident: about 5,000 albums, sorted alphabetically by genre, and dozens of guitars, picked up from as far away as Europe and Japan.

And sure, Ollinger — to quote rocker Steve Miller — could have taken the money and run, by sinking his insurance settlement into an online subscription service such as Sonus, which would allow him to listen to practically any song under the sun. Except that wouldn’t be the same as running his fingers through shelves of albums, trying to decide if he was in the mood for Pink Floyd’s Animals, Jethro Tull’s Crest of a Knave or the Allman Brothers’ Brothers and Sisters, three of his long-time faves.

“Besides, it was never about ‘how much?’” he says, preparing to drop the needle on a new album by Future Islands, an American synthpop band his daughter introduced him to. “I mean, how do put a dollar figure on sentiment?”

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Mike Deal started freelancing for the Winnipeg Free Press in 1997. Three years later, he landed a part-time job as a night photo desk editor.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.