Hybrid memoir haunted by history

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Stylistically excessive writing that impairs ready comprehension can torpedo a thought-provoking book.

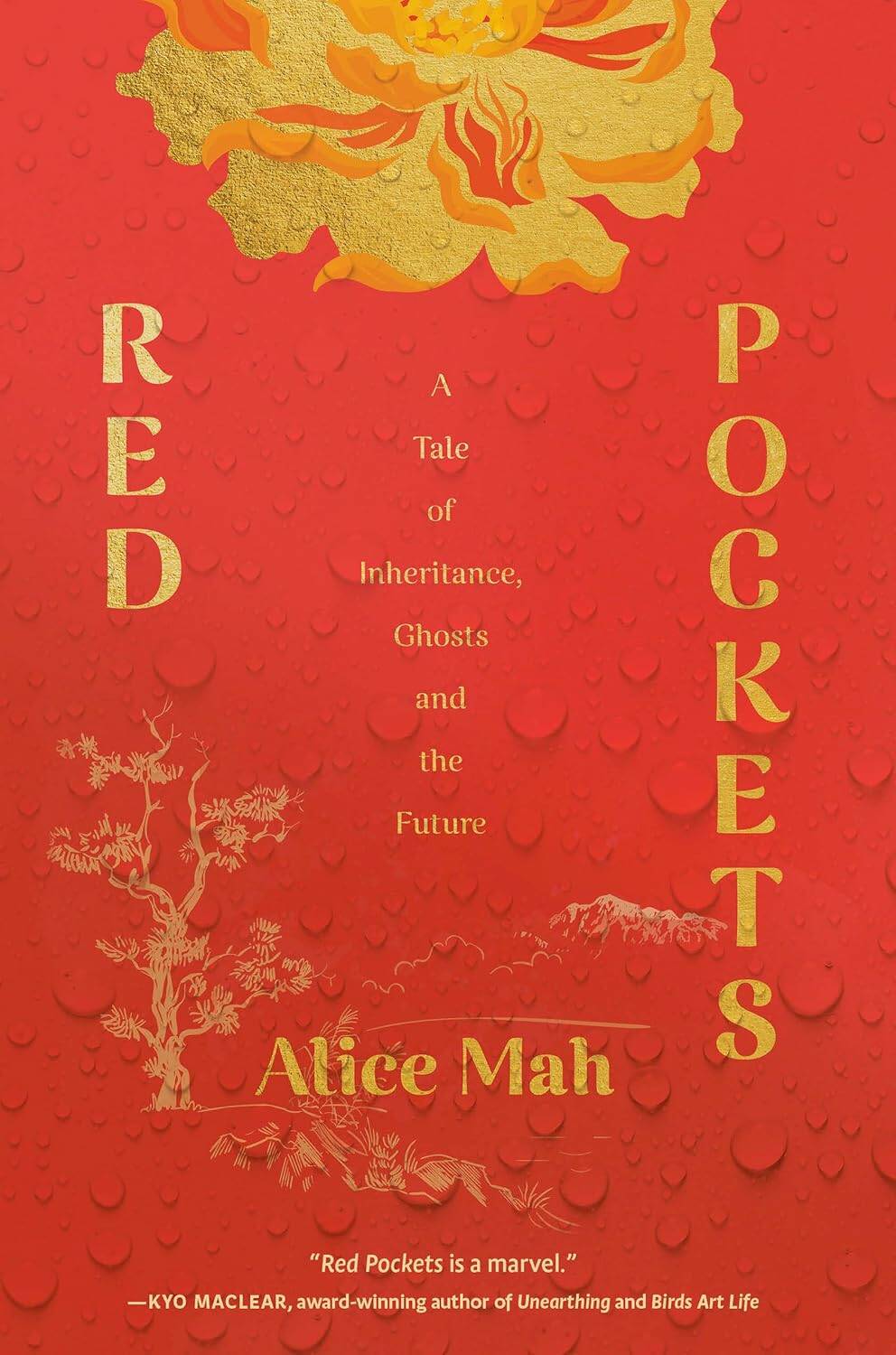

Red Pockets is a case in point.

Author Alice Mah is a Chinese-Canadian professor of urban and environmental studies at the University of Glasgow who grew up in Cranbook, B.C. Red Pockets is her first book.

Red Pockets

She’s of mixed race, her father being of Chinese descent, her mother Caucasian. Growing up in southeastern B.C., she and her siblings were often mistaken for local Wet’suwet’en Indigenous people by townspeople.

Ancestor worship is a hallmark of south China culture. Every spring people are supposed to return to their home villages to offer food and incense to prevent their forebears from becoming angry “hungry ghosts” that cause misfortune or illness to their living descendants.

Ninety years after her grandfather’s last visit, and 50 years after her last village relative died, Mah returned to her ancestral home in Guandong province of south China to remedy the family’s chronic absence and neglect.

The memoir begins by dexterously exploring her family history, aided and abetted by singular reflection. But latterly, it spirals downward into exasperating repeated scratching at the author’s psychic scabs.

The book’s overarching trope is those “hungry ghosts.”

It’s used as a metaphor for any and all personal despair and psychic trauma, pending or realized, as well as environmental depredations and climate change — all-purpose usage that fast becomes tiresome.

Her account of her journey in the first third of the book is nicely rendered, supported by insightful meditations on her family’s immigration to Canada and her ancestral legacy. There’s lots to admire early on in her unorthodox mix of memoir, history and environmental crises.

Mah is most eloquent when she abandons self-absorption for historical narrative that is also family narrative.

She deftly sets up horrific macro-political events like Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and then makes its horrors micro by bringing it home to her family.

“During the Cultural Revolution, mass killings were widespread in villages across China, particularly in the South,” she writes. “According to the Guangdong Province Gazetteer, 42,237 died of unnatural causes due to random beatings, random killings, random detentions random struggles.

“There were no Red Guards in the villages like there were in the cities. Instead, as the sociologist Yang Su writes, ‘neighbours killed neighbours.’ They pushed their ‘class enemy’ neighbours off cliffs and bludgeoned them with clubs and hoes.”

That backstory frames the revelation that her great-grandfather’s second wife bought a parcel of land after the Sino-Japanese War but “killed herself during the Cultural Revolution for fear that she’d be publicly humiliated and tortured for owning some land.”

Her seeming object is to gain transcendent insight into her family’s history as part of the diaspora of the early 20th century that saw so many Chinese immigrate to Canada.

And when her narrative connects to her ancestral links or political or ecological matters it sings. But when it doesn’t, it mumbles.

Unless you are an adherent of Buddhism or Zen Buddhism, many of her spiritual musings in latter parts of the book are apt to come off as esoteric, or worse, affected.

Red Pockets is a novel attempted hybrid literary work that’s undone by a penchant for purple prose.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.