Keeping it cool

Protagonist perseveres in stellar slice-of-life graphic novel

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

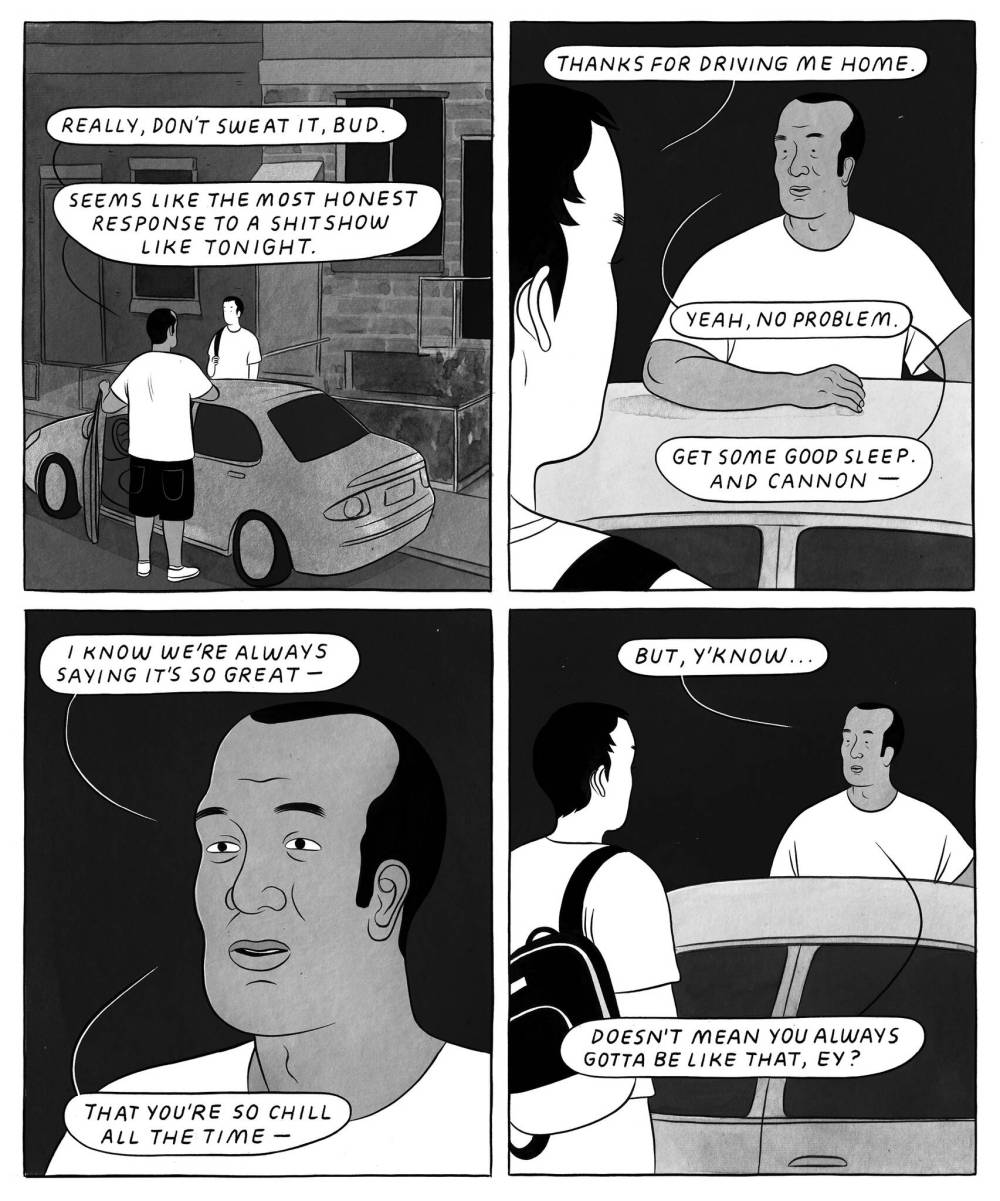

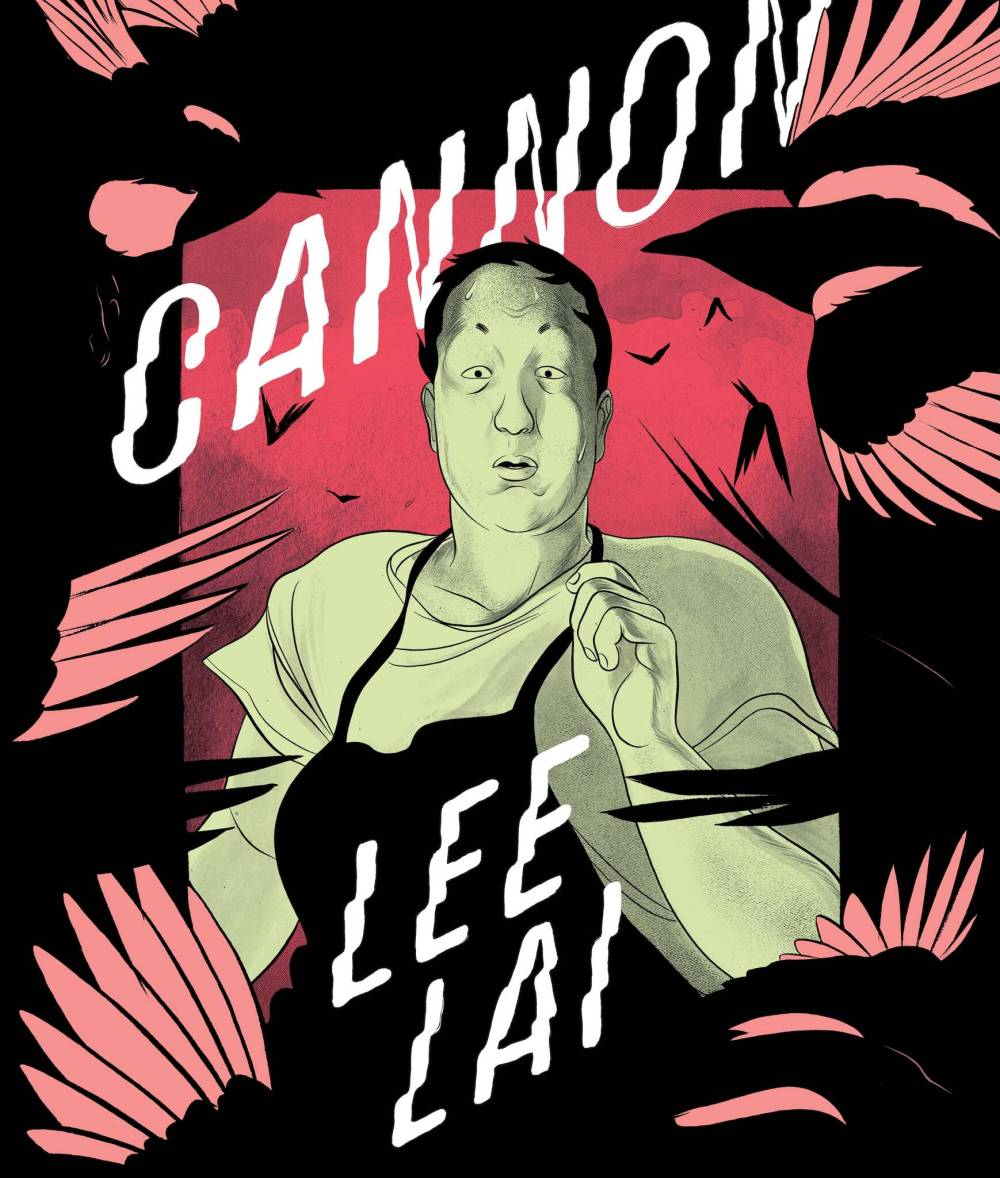

Lee Lai’s masterful follow up to 2021’s acclaimed Stone Fruit begins with an explosive scene, akin to the result of a loose cannon. The frenetic destruction presented in Cannon’s opening pages immediately invites assumptions about the kind of person who caused it.

But when introduced to the eponymous Cannon, it’s obvious that her nickname is ironic; her ability to keep a cool head and compassionate demeanour in stressful situations are her defining characteristics.

Nevertheless, even the most unflappable person may still hold long-simmering tensions underneath their calm exterior, the repercussions of which make up the brunt of this deftly layered slice-of-life graphic novel.

Cannon’s story is presented primarily in a sparse black-and-white palette, with four panels per page crafting a literal window into both her outer life and the way she compartmentalizes her feelings. Brief moments of solitude are dissociative; she listens to meditation podcasts while hustling to or from work, and imagines a flock of black birds taking over the room during extreme overwhelm.

Even so, Cannon stays dependable and willing to put others’ needs ahead of her own. She is an outstanding employee to a questionable restaurateur, a dutiful daughter and granddaughter who provides care to her difficult, aging Gung Gung, and the long-suffering best friend to novelist Trish, whose own professional stresses cause a rift in their friendship.

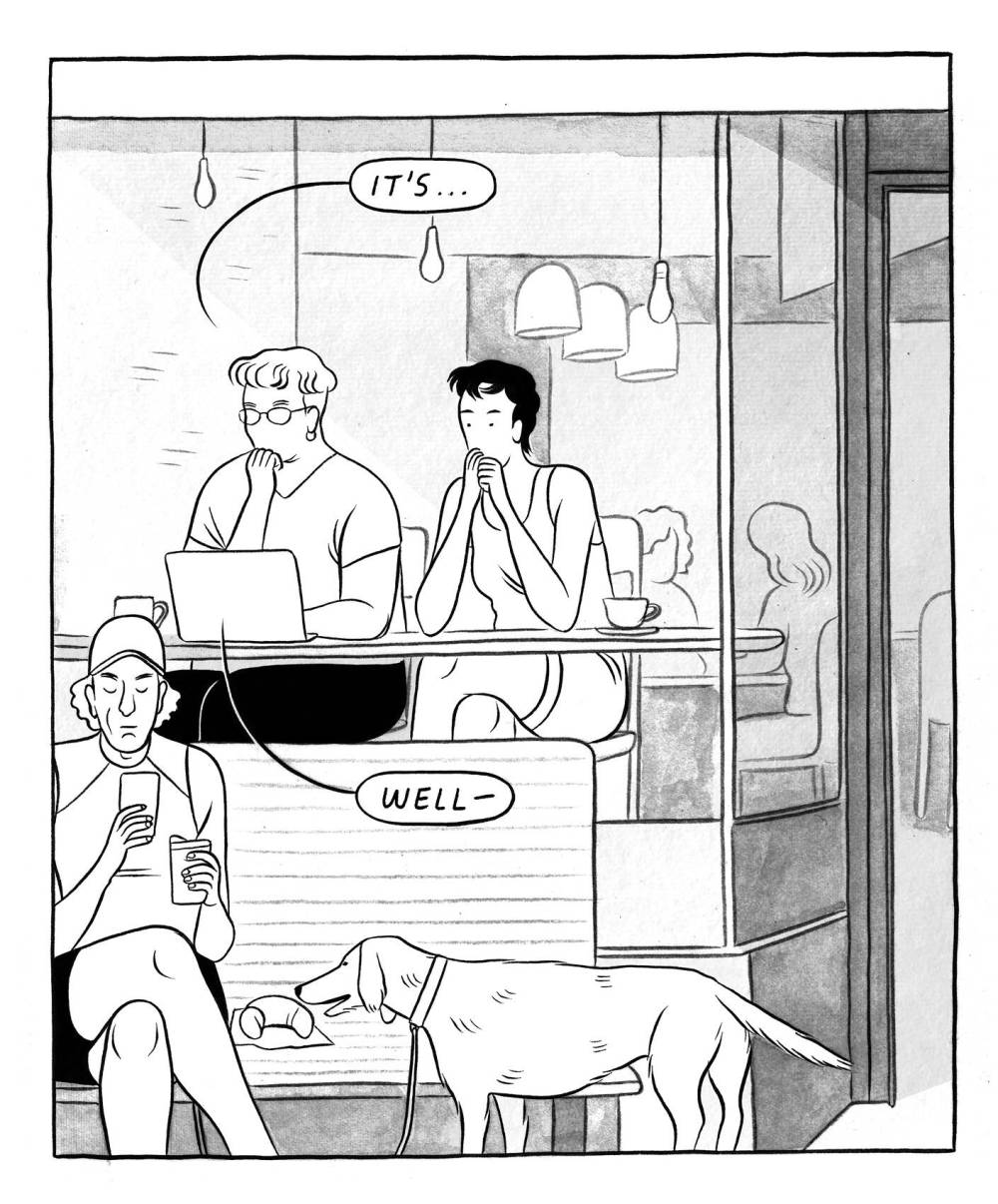

The inevitable fracturing of Cannon and Trish’s longstanding friendship is significant, especially given its origin of shared experience as the only queer first-generation Chinese kids in their small town. Now in their late 20s and living in Montreal, the pair’s complicated kinship largely reflects their differences instead of the sameness that initially brought them together; though they are both queer, they are varied in their sexualities (remaining platonic friends for the duration of the book), and navigate romantic relationships differently.

Scenes between the two find Lai keenly attuned to body diversity and facial expressions, while portraying Trish and Cannon’s different communication styles through missed calls, unanswered texts and ingenious, overlapping speech bubbles. When Cannon speaks, Trish tends to talk over her, often frustrated with her friend’s all-consuming familial loyalty (which she also takes insidious advantage of.)

Lai’s interplay between language and selfhood is also stunning, shown through pointed dialogue and its visual portrayal on the page. Trish’s vocation as a writer affords the story a metafictive layer of introspection — for example, when a mentor describes her identity as an in-demand “piece of a cultural niche,” Lai is likely mindful of how her own writing could be similarly labelled. Trish, however, scorns the unspoken expectations for LGBTTQ+ and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour) stories while still mining her friend’s life for details, creating a jarring wall of Post-It notes that turn Cannon’s complex family dynamics into deconstructed character traits and plot points.

Cannon

Cannon’s daily life also involves multiple spoken languages, highlighted with word balloons in both Cantonese and English (at Gung Gung’s), or English and French (at the restaurant, only enhancing the pressure-cooker atmosphere and tense dynamics of overworked kitchen staff). The dual-language contrast within the same panel is also a visually striking mirror into Cannon’s quick adaptability, and the resulting mental toll.

Lai also includes food as a secondary, illustrated language, as beautifully rendered panels hone in on Cannon’s cooking in her professional and personal life. That Cannon’s efforts often go unappreciated, especially by those close to her, further devalues her self-perceived worth as being rooted in service, or food-as-care.

Though Cannon might be cared about, she is rarely cared for. But as evidenced by her family history, her self-abandonment can’t simply be cured by cutting ties to people without processing her feelings. Lai’s opening pages, and Trish’s presence in them, only gain emotional heft as Cannon retroactively struggles to maintain relationships while running on fumes and self-neglect.

Though there is no solace to be found in isolation, genuine reciprocity and open communication remain a hopeful path to Cannon’s emotional sustenance.

Nyala Ali writes about race and gender in contemporary narratives.