Clutches of religious indoctrination leads to fraught mother-daughter relationship

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

For much of her life, Tamara Jong was a Jehovah’s Witness.

Its strictness and structure gave the Montreal-born writer a sense of belonging, meaning and, perhaps most powerfully, stability — things her chaotic, alcoholic mother who raised her in religion and her distant (and eventually absent) father could not offer her.

But as she got older, religion stopped being a comfort. It had become a cage.

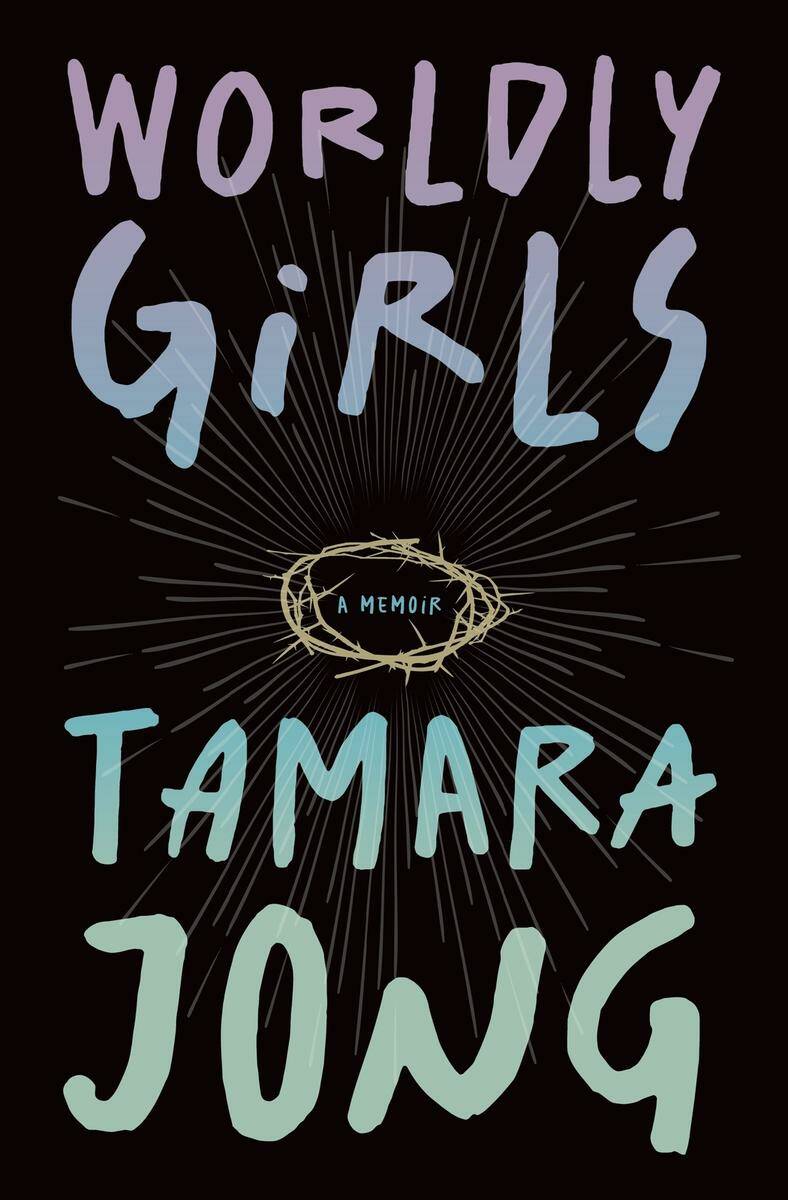

In Wordly Girls, her striking debut memoir-in-essays, Jong unpacks her indoctrination and subsequent disillusionment with the religion that formed so much of her identity — as well as her adult struggles with depression, infertility and estrangement — with remarkable vulnerability.

It’s a slim volume, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a short read. Jong’s prose — spare, precise, unflinching — invites you to spend time with it. She’s not afraid to wrestle with messy, complicated feelings and concepts on the page and resists tidy, bow-wrapped endings — especially when it comes to her journey with infertility and becoming a stepmother, and her fears about what kind of mother she’d be owing to the mother she had — which is what the best essays do. Some may have benefitted from a more narrative treatment (less recounting and more storytelling), but that’s a minor quibble.

Indeed, the heart of the book is her fraught relationship with her Ma, who dies suddenly and tragically in a drowning accident. By that point, Jong and her mother had been estranged for years; Jong’s mother was cast out of Jehovah’s Witnesses for smoking, and Jong, still deep in the faith, limited contact with her.

Jong’s memories of her mother are in the vividly wrought details. She describes a watch that belonged to her mother she receives after she dies, given to her in a plastic sandwich bag, its “stretch band that used to catch the little blond hairs on her wrist.” She writes about being able to conjure the smell of her mother’s purse (Du Maurier cigarettes and Wrigley’s gum). She writes about a small, wordless act of kindness when her Ma repairs Panda, her beloved bear, that she thought was thrown away. Ma was a mother but she was also a woman, and through time and forgiveness, Jong is able to remember her as both.

It’s the penultimate essay, Leave-Taking, that puts that point into stark relief. Jong is writing to her mother — “after you drown” — and imagines her last moments based on the details she received from her brother. It’s an absolutely stunning piece of writing, not just for its prose, but for its compassion.

Jen Zoratti is a Free Press arts writer and columnist.

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.