Disordered care

Patient activists seek movement in diagnosis, treatment of FND or functional neurological disorder

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Functional neurological disorder (FND) is often described as an invisible illness.

The condition affects how the brain processes information and communicates with the body, resulting in a wide range of physical and neurological symptoms that differ from person to person. Unlike structural brain issues — such as tumours, strokes or lesions — functional neurological disorder (FND) symptoms don’t show up in conventional diagnostic testing and imaging.

This common, gendered disorder traces its roots to hysteria; yet, centuries later, its causes and mechanisms remain largely unknown.

Winnipeg academic Jen Sebring is among those working to make this invisible illness more visible in Canada.

The 28-year-old started experiencing dissociation, difficulty walking, balance issues and seizures during her undergrad in 2015. She was referred to a neurologist, epileptologist and other specialists, but didn’t receive a formal FND diagnosis until 2019 after learning about the condition and bringing it up with her doctor.

“You get kind of a non-diagnosis, like, ‘We know it’s not this.’ And then they tell you to reduce your stress. There’s no followup or treatment pathways for people,” she says.

Unable to find adequate care in Manitoba, Sebring travelled to Colorado for nervous system-based treatment from a neuropsychologist specializing in FND.

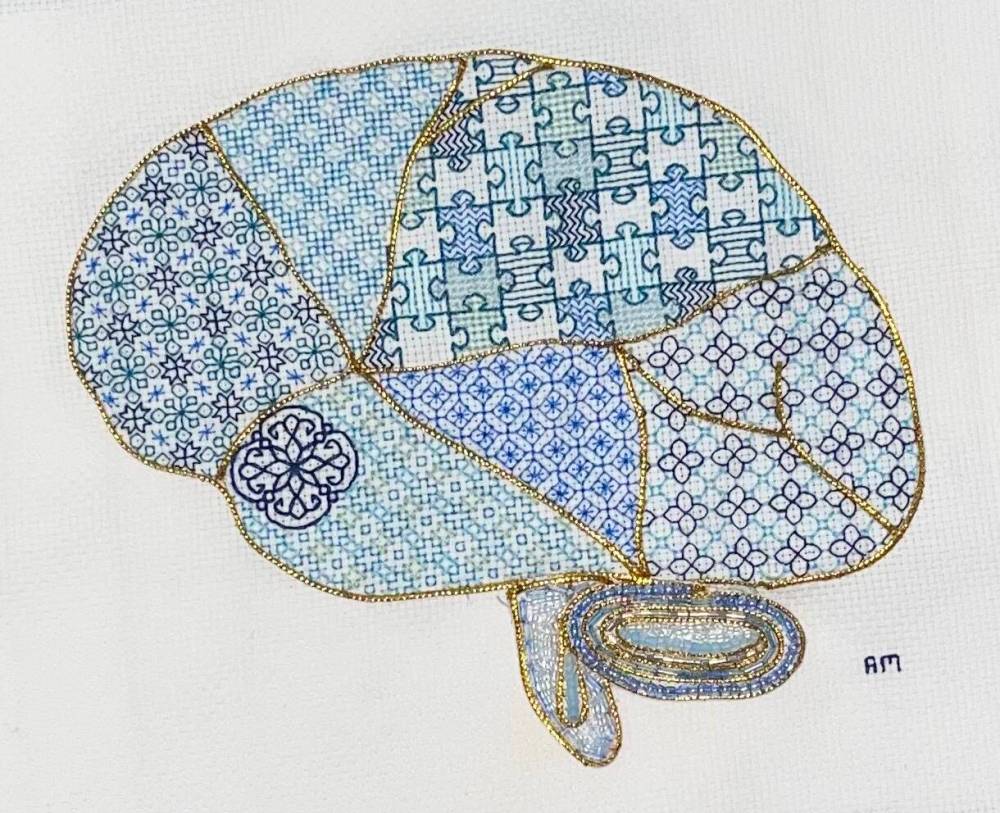

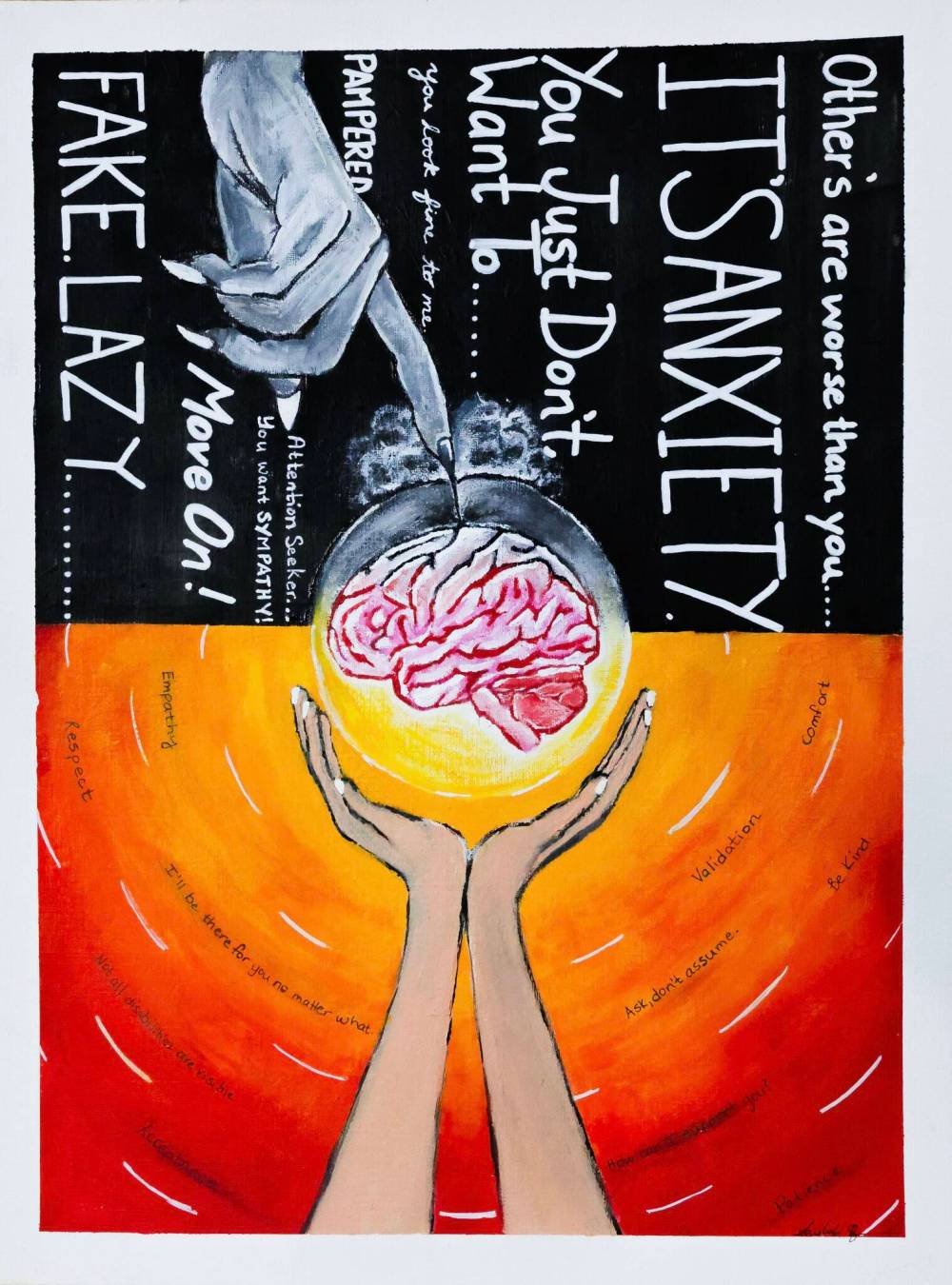

The critical social scientist and PhD candidate at the University of Manitoba has since dedicated her graduate research to the condition and recently launched Undoing Disorder (undoingdisorder.ca), a website showcasing artwork and reflections from fellow patients across the country.

Art seemed like a fitting investigative tool for Sebring, who found photography and self-portraiture helpful in processing her own diagnosis. She conducted interviews and invited participants to illustrate their diverse symptoms and often traumatizing experiences navigating the health-care system.

“Care is a huge issue and awareness is a huge issue so I’m trying to see how people are managing and what that means for them. I was struck by the heaviness of people’s stories,” she says.

The resulting paintings, collages, photographs, drawing and embroidery depict pain, frustration and the relief of finally receiving a diagnosis, which takes an average of seven years for FND and usually involves multiple specialists.

In reflections, participants described feeling validated and empowered by the art-making process, especially as a way to communicate when dealing with fluctuating cognitive capacity and debilitating physical symptoms.

“It was a really meaningful experience and I think people got a lot out of it,” says Sebring, who hopes to share the project’s findings with clinicians and plans to develop art-based resources for health-care professionals in the future.

Education is a major priority for Dr. Gabriela Gilmour, a neurologist and program leader of the Functional Movement Disorder Clinic at the University of Calgary.

The clinic opened in 2023 and was born out of a lack of patient and physician resources in Canada.

SUPPLIED

Lift the Weight or Deepen the Wound, a painting by Vaishali Sharma representing stigma and compassion.

“I work with a lot of trainees and we’re working very hard to help them recognize and understand what FND is and how to diagnose it,” Gilmour says, adding awareness is scarce but improving within the medical field nationally.

Functional neurological disorder is the second most common reason for referral to a neurologist behind headaches, according to a 2010 UK study.

The brain disorder is akin to a computer software issue — the physical “hardware” of the brain looks normal in diagnostic testing, but the neural networks are malfunctioning, Gilmour says.

Common symptoms include motor issues, such as limb weakness, difficulty walking, tremors and involuntary movements, as well as neurological complaints, including non-epileptic seizures, pain, dizziness, fatigue, speech problems, brain fog and sensory issues. It can manifest at any age as one or multiple symptoms.

An estimated 70 per cent of FND sufferers are women, but the reason for this gender divide is unclear.

Current research points to a mix of biological, psychological and social factors. Hormones, physical and emotional abuse, childhood trauma, injury, stressful life events and other neurological disorders may play a role in triggering FND.

The modern research gap is due, in part, to age-old medical misogyny.

Markers of FND have been classified as hysteria for much of human history.

Stemming from the Greek word for uterus, hysteria diagnoses were based on the misguided belief that a “wandering womb” caused a wide variety of unexplained and presumably imagined health issues in female patients.

Female hysteria, specifically, became a popular and dismissive catch-all diagnosis within neurology in the late 19th century. It was officially removed from diagnostic use in the 1980s.

“This condition has always existed. It was, unfortunately, a very stigmatized condition, so I think what we’re seeing now is an echo of this historical context,” Gilmour says.

Since FND falls between the worlds of neurology and psychology, it has also suffered from a traditionally siloed medical system.

SUPPLIED

Finding a Way Through by Jocelyn Bystrom reflects the journey of her FND diagnosis.

“When no single specialty is taking ownership, then there isn’t research that is happening and there aren’t resources and treatment strategies being developed,” Gilmour says.

The disorder is diagnosed through a combination of personal history, symptoms and movement tests to determine if the issue is physical or related to the signals the brain is sending to the body.

Treatment often involves neuro-physiotherapy and psychotherapy with the goal of retraining the brain’s neural pathways. It’s possible to reverse symptoms completely through rehabilitation.

“The earlier somebody gets a diagnosis after symptoms start, the better,” Gilmour says.

Unfortunately, the road to diagnosis in Canada is usually long and winding.

Susi Brown spent six years in medical limbo before learning she had FND.

“I believe that if I had been given the diagnosis in a timely way, if I had been given access to the multidisciplinary team that this condition requires, I wouldn’t have had to suffer the way that I have,” she says over a video call from her home in Montreal.

Brown’s symptoms — mobility problems, light sensitivity, migraines, cognitive challenges, auditory and sensory issues — developed after she was hit by a taxi while crossing the street in 2013.

Her condition continued to worsen as she was shuffled between brain injury clinics, neurologists and psychiatrists.

Brown, 55, had to leave her job and spent days bedbound in complete darkness when her symptoms surged.

Without a diagnosis it was difficult to access disability benefits and make health insurance claims.

“We consulted with so many doctors, specialists, sub-cent specialists, and a lot of them would say, ‘We’ve never seen this before,’” she says.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS Jen Sebring, a PhD candidate at the University of Manitoba whose research focuses on functional neurological disorder (FND), with art created by people with FND as part of a series of art workshops on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. The patients created pieces that show what their symptoms feel like as part of the diagnostic process. For Eva story. Free Press 2025

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

University of Manitoba PhD candidate and functional neurological disorder sufferer Jen Sebring is studying the condition and has created a group art project on the subject, called Undoing Disorder.

She was diagnosed in 2019 after seeing a movement disorder neurologist who specialized in Parkinson’s disease — a condition with symptoms similar to FND.

Brown’s treatment journey has been piecemeal and she continues to bounce between rehab specialists due to availability. She’s currently on the wait-list for a multidisciplinary FND outpatient program in Toronto.

Feeling frustrated and isolated, Brown and her husband started FND Together, a registered charity and online community for patients to connect and share resources. The couple closed the charity last fall after five years in operation, but have continued to maintain a platform as a Facebook group (FND Together Canada) with more than 600 members across the country.

Brown says more work is needed to improve FND diagnosis and treatment in Canada, but she’s hopeful new research and awareness efforts, such as Sebring’s Undoing Disorder project, will help move the needle.

Gilmour is also feeling hopeful.

“I really see us as being in a new age of FND,” she says.

“A lot of research is happening to really try to understand the mechanisms and what’s happening in the brain. And as we learn more, we develop new treatment strategies and we have better outcomes for patients.”

winnipegfreepress.com/evawasney

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.