Fight the algorithm

Mixed-media artist works slowly to examine rapid ramifications of social media

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Charlotte Sigurdson has her hands full.

The 37-year-old mother, painter and sculptor is talking on the phone, while moments earlier she was sewing one.

A sculptural phone, that is, for her exhibit Your Attention Please/ Votre attention s’il vous plait, which opens Jan. 15 at La Maison des artistes.

Supplied

Charlotte Sigurdson gave up being a lawyer to be a full-time artist.

“It’s taken a year to do, and it’s this really slow medium. The idea is that you would just scroll past this on the same device,” she says of the goldwork embroidered piece.

Art, and what the Internetification of life has done to art, isn’t the main subject of this show. That would probably be too navel-gazing for work that critically examines online echo chambers, self-obsession, rage and the loneliness they create.

But for an artist working with traditional, even antiquated, mediums (Sigurdson is probably best known as a maker of billowing, baroque-like dolls), she can’t stop thinking about her phone — or checking it — and this obsession is stamped on her work.

“I’m susceptible to being chronically online, so have to create strict guidelines,” she says. “I was a lawyer, so I didn’t go through the traditional (art) training. Social media was a way that I could build a career without any of that.”

But, like many, she also worries that social media devalues art.

“I find there’s a juxtaposition between the time I take — hours and hours and hours — and then how quickly it’s just scrolled past. Things become disposable with shorter attention spans, so people can’t really think deeply about the work,” she says.

Supplied

Guess How Much Time I’ve Spent on My Phone, gold work, textiles and beadwork.

While some of Sigurdson’s criticisms may seem commonplace today, they echo a tradition that predates social media.

Artists and theorists have had mixed things to say about technology’s effects on art since seemingly forever, and with growing gusto since at least the age of printmaking.

In 1935, Walter Benjamin famously observed that “mechanical reproduction” democratized art consumption, while also stripping the original of its spiritual “aura” by producing potentially limitless copies.

This vision seems especially prophetic today in the era when the internet creates even fewer barriers to reproducing and circulating images, and art is often made digitally.

Sigurdson rolls her eyes at the way NFTs (non-fungible tokens) have tried to regulate — and capitalize — on this new art world where everything solid seems to melt into thin air.

Supplied

A Painting of a Person Using a Mindfulness App, oil on canvas

They treat one file of digital art as that work’s “original,” with an internal blockchain token working as a sort of “article of authenticity,” as a new vehicle for the art market.

At the height of the craze in 2021, the highest bids on NFT art were in the tens of millions. Within a year, it was reported that the majority of NFTs were worthless.

“It’s a scam. I get like, 30 emails a day — people being like, ‘I’m gonna buy your art with NFTs.’ I can’t even keep up with things like that. I’m such a tactile person. I could never do AI art or even digital art. I need to touch things. That’s a really important thing for me,” Sigurdson says.

If intimacy with objects is central to her practice, intimacy with others, or the lack thereof, is central to her work’s themes.

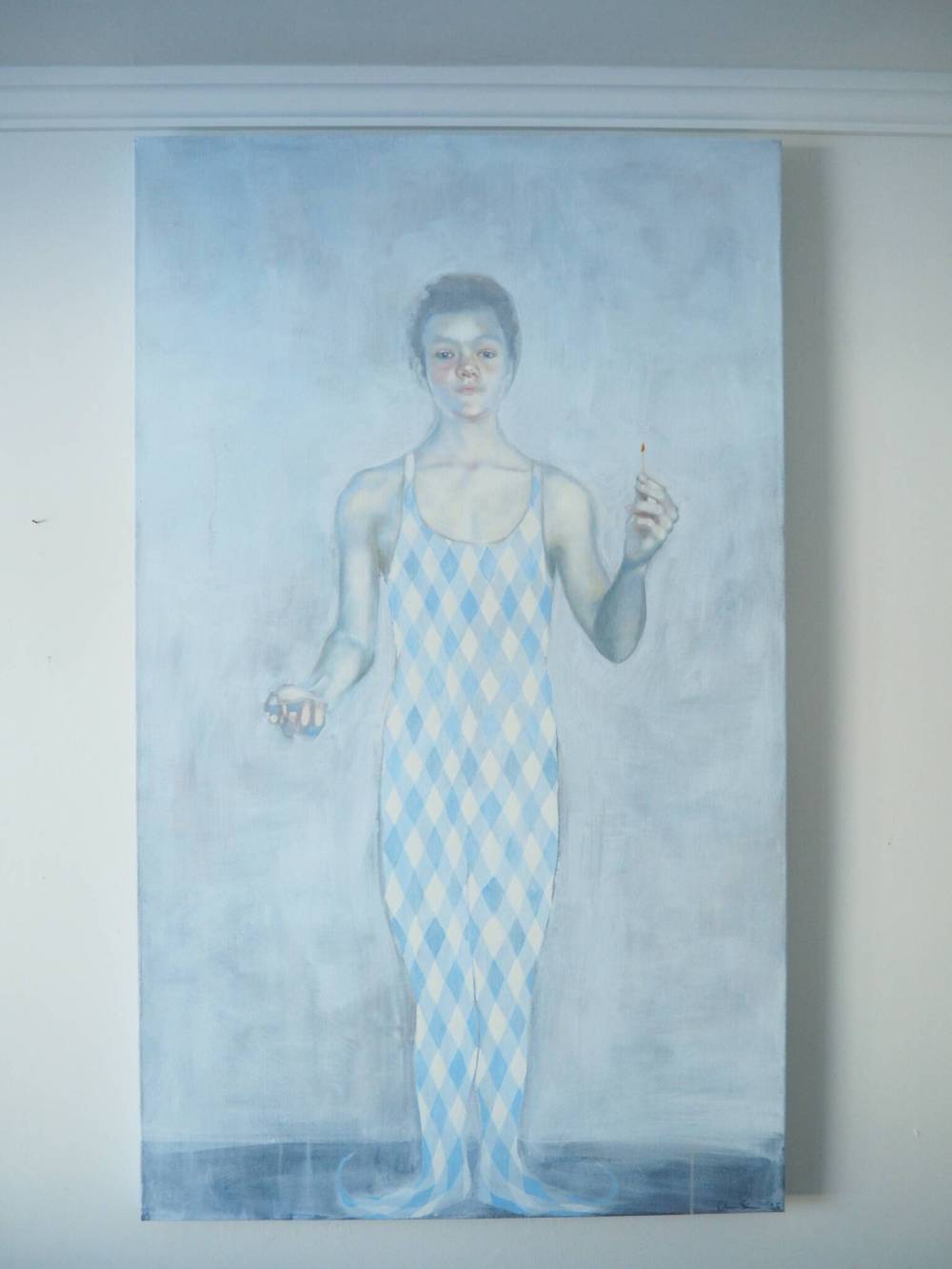

One piece, The Arsonist, deals with a surprisingly common phenomenon: volunteer firefighters, usually men, deliberately engaging in arson.

Sigurdson was especially interested in the case of a young Australian man who reportedly started a forest fire so he would have an excuse to bond with other firefighters, facing the disaster as one.

Supplied

The Guru is made of wood and textiles.

“It became a metaphor for boys and men doing destructive things when they want human contact, when they want community. I saw a lot of parallels with the way that social media has gone with disconnected boys, and I think it comes out, sometimes, in these really horrible ways,” she says.

Sigurdson is troubled by how extremists are operating with growing openness on social media, emboldened in part by pseudo-communities online and the echo chambers they create.

Long gone are the days of white supremacists lurking at the internet’s fringes. These days extremists, whatever their political cause, appear to be everywhere on mainstream social media, she says.

She adds an optimistic twist, suggesting the algorithm may give the false impression that these voices are more prevalent than they actually are. A house of mirrors can trick even those who think they’re peering in from the outside.

The Algorithm, a papier-mâché sculpture, addresses these distorting feedback loops and what they do to our sense of self and world.

Supplied

Some Say Google is God, oil on canvas

“I’m obsessed with the algorithm,” she says.

“It’s giving, I would say, the darkest parts of you. I watch stuff that I don’t like because I’m upset by it, and then, it keeps giving it to me. And then it’ll change the way I think. And then you talk to people in real life, and you’re like, ‘No, people aren’t thinking this.’ Like, this isn’t everybody.”

After leaving law to become an artist, Sigurdson worried online media might become her main window onto the social world. Painting and sculpting are solitary activities, and the demands of parenting kids under 10 can be full-on, but she’s found both to be sources for new bonds.

“Winnipeg has created a really beautiful little arts community. It’s a huge part of my social life,” she says.

“Kids bring you into the world in a really forceful way. I actually often think about what I’m gonna when I don’t need to sit at their basketball practice anymore.”

Leafing through the leisure catalogue in search of activities for her kids also gives her ideas about what she might do with this extra time, beyond making more art.

Supplied

The Arsonist was inspired by a man who wanted to bond with firefighters.

“I’m going to sign up for diving lessons (one day), ” she says. “Being a kid gives you a sense of community and connection — all the fun activities you do. When my kids are older, I’m gonna just become the kid.”

winnipegfreepress.com/conradsweatman

Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the Free Press full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.K. and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including The Walrus, VICE and Prairie Fire. Read more about Conrad.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.