Ice-crusted holy grail

Interlake explorer leads TV viewers on a modern Viking quest

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Winnipegger Johann Sigurdson, a protagonist of the Quest for the Lost Vikings TV series that premièred on Super Channel Quest last Sunday, identifies with a long line of Norse explorers.

A millennium-long line, to be precise.

“We actually descend from folks that were likely here back from the time of the L’Anse aux Meadows: Thorfinn Karlsefni and Gudrid Thorbjarnardottir,” says Sigurdson.

Supplied

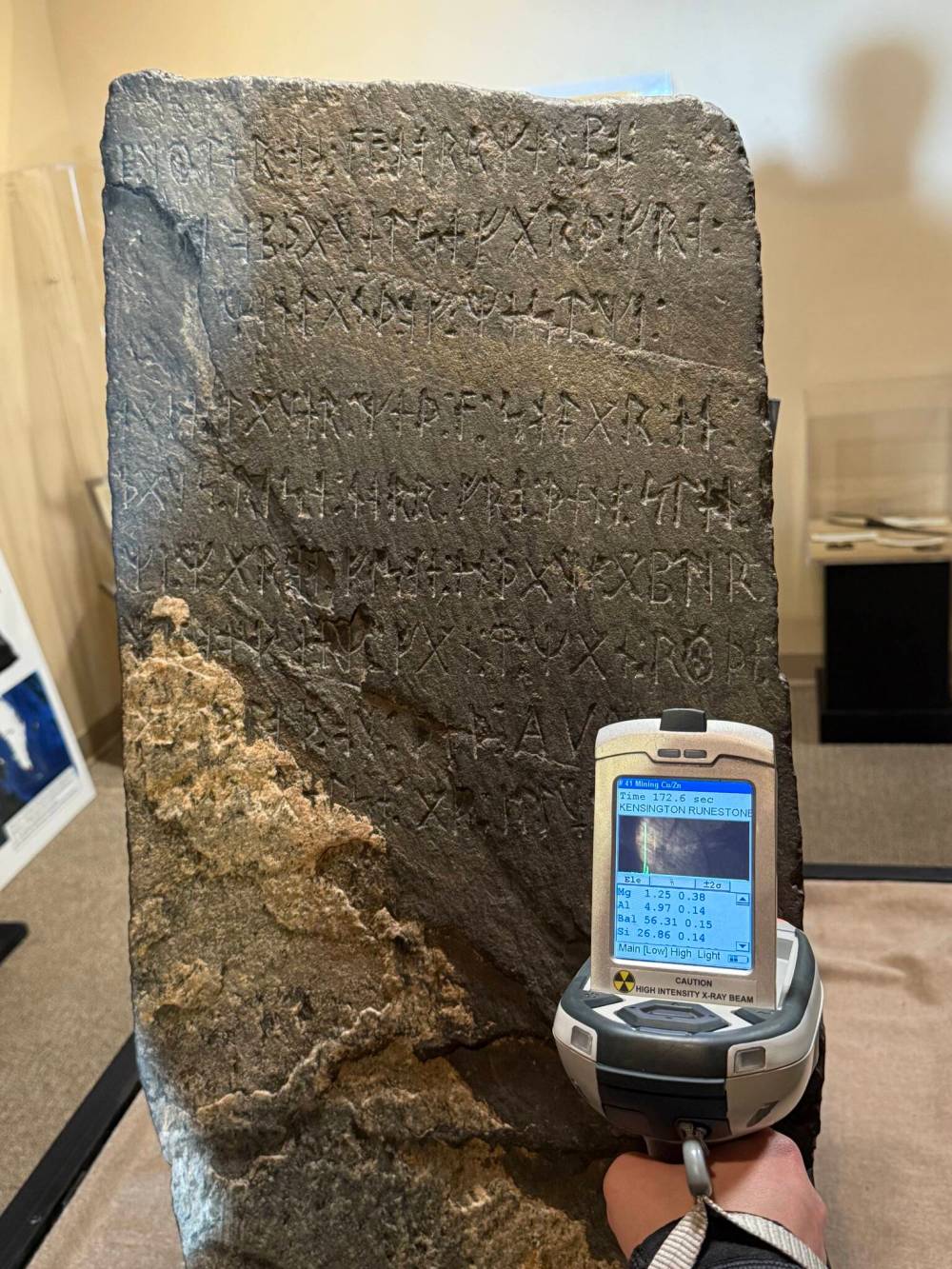

Episode 4 of Quest for the Lost Vikings takes Johann (left) and Jo Sigurdson to Alexandria, Minn. to investigate the Kensington Runestone.

The latter two are now recognized as early Icelandic explorers of North America, while L’Anse aux Meadows is an archeological site in Newfoundland of Norse settlement from about 1,000 years ago.

Sigurdson is a fellow of the famous Explorers Club and the Royal Canadian Geographical Society along with series co-stars David Collette and Mackenzie Collette. Together, roughing it across landscapes icy and craggy in scenes gloriously captured by local production company Farpoint Films, the trio and their colleagues explore exotic terrain both physically and conceptually.

The series pursues a provocative claim: that medieval Norse exploration of North America didn’t stop in Newfoundland but extended much deeper into the continent.

“A lot of people, for a long time didn’t believe the Sagas (but there’s) a lot of history, a lot of facts there, and so it just depends on your perspective,” says Sigurdson.

“We consider ourselves truth seekers, and we’re truth seekers about our own ancestry.”

The Icelandic Sagas, composed around 1200-1300, are a wellspring of historical insights and cultural myth, and one of the world’s most significant medieval documents. Despite their dry prose, they’ve nourished the worldview of romantic writers from Walter Scott and J.R.R. Tolkien to more problematic mythmakers like Richard Wagner and Guido von List.

But most importantly, for all their supernatural flourishes, they’ve helped to make the Dark Ages a little less dark for contemporaries: shedding light on everything from Iceland’s 9th-11th centuries’ culture and proto-democratic political system (the Althing), genealogy, family feuds and migration patterns.

In that last connection, the Vinland sagas describe Viking explorers sailing westward of Greenland and settling in an area called “Vinland.” It wasn’t until the 1960s that the L’Anse aux Meadows was uncovered, confirming that the Norse did indeed make life in North America well before Christopher Columbus, transforming certain parts of myth into fact.

Through Fara Heim, which he established with David Collette over a decade ago, Sigurdson and his colleagues have worked to expand our knowledge of Norse exploration of North America.

The organization’s website lists, among its advisory board, a number of PhDs with expertise in the areas of archeology and geography, not to mention Icelandic-Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin, famous for his mythopoetic visions of New Iceland and Winnipeg.

Meanwhile, Sigurdson spent his career in biology and resource management for the federal government, further exploring the Arctic and subarctic regions through Fara Heim.

“We’ve been doing it for about 10 or 15 years in the Hudson Bay coast, several times, looking for Viking things and the film company contacted us and said, “How’d you like to do an eight-episode documentary?’” he says.

Supplied

Mackenzie Collette uses a spectrometer to do an elemental analysis of Minnesota’s Kensington Runestone, which features in Episode 4 of Quest for the Lost Vikings.

The series’ trailer captures the intrepid, white-haired Sigurdson and David Collette, and other colleagues and friends of different generations, slogging through waist-deep snow, attempting to rescue semi-capsized tundra buggies and searching for holy grails of a more pagan sort.

Sigurdson says their team — employing a range of methods, from state-of-the-art scientific scanning to researching archives and Indigenous oral histories — made an explosive discovery.

“We found an artifact that’s the oldest of its kind in North America, and it dates to the time around the time the Norse Viking explorers were here… It was found along an obvious exploration route in Manitoba,” he says.

Sigurdson would prefer that people watch the series — episodes come out weekly — rather than reveal more details, but says that their discovery was confirmed by relevant experts.

Beyond the series’ exploration of history and counter-history, it’s also about family and community. Manitoba boasts the world’s largest Icelandic population outside of Iceland.

Many of them celebrated New Iceland’s founding 150 years ago this fall — recognizing a moment when more modern Icelandic settlers first landed at Willow Island just outside Gimli to make life, despite harsh conditions, in what was then still a remote, inaccessible region.

Quest for the Lost Vikings taps into Canadian Icelanders’ abiding interest in their history and culture.

“My nephew David is 20 years younger than I am, and my son and his daughter are 20 years younger than he is. And so, it’s like three generations, right? It was wonderful to spend time with your family doing something, tracking something you enjoy,” he says.

winnipegfreepress.com/conradsweatman

Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the Free Press full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.K. and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including The Walrus, VICE and Prairie Fire. Read more about Conrad.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.