Apocalypse now (and then)

Revisiting evangelical pop-culture ephemera melds careful critique with moving memoir

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

This is not just a strikingly timely book, it is also a fascinating, funny, upsetting and, in the end, beautiful one.

What Joelle Kidd has done here is rather difficult to categorize.

At first blush — manifest immediately in that very carefully crafted subtitle — Jesusland presents itself as a memoir. Daughter of a Scottish father and a Mennonite mother, the millennial Kidd was initially raised in Eastern Europe, but her most formative years were spent in an evangelical Christian school in Manitoba. (She now lives in Toronto.)

Jon Owen photo

Jess Kidd’s debut book-length work of non-fiction chronicles her formative years spent in an evangelical Christian school in Manitoba.

Those years, squarely aligning with the aughts, are the focus of her unforgiving yet dear reflections here. We learn only sparsely of her family but deeply of her primary and secondary education, of her awkward immersion in early internet social worlds, of her earnest, thinking devotion to her “Purity culture” faith and of her personal and social awakenings as she grows into adulthood.

At second blush, however, Jesusland announces itself as a work of some scholarship. This is, to be clear, not the work of a pure, removed academic. There are footnotes, yes, but these are fleeting and more anecdotal than bibliographic — in other words, they are charming rather than demonstrative.

But Jesusland is not at all unsubstantiated musings and moody ramblings either. On the contrary — appended to the substantial nine chapters are no fewer than 24 pages of carefully organized secondary sources, many of an obviously scholarly nature.

More, Kidd almost cruelly assigned herself an enormous amount of pop culture homework. We feel her pain, her boredom, her disappointment as she repeatedly tells the tales of slumping through so many awful old made-for-TV “films” (read: crass commercials), of wilfully listening to so many vitriolic sermons and disturbing revival hours, of flipping through so many evangelical teeny-bopper glossy mags, of reading stacks of evangelical pop novels and on and endlessly on.

Not only did she do this dreary homework, much of it constituted repeat work — viewing, listening to and reading things she had absolutely cherished as a teen, but now can barely stomach as a well-educated, aware, astute 30-something.

And with lovely, endearing wit, Kidd spins little stories of tracking down and attending these pop culture products anew. Sometimes she goes at the evangelical pulp with bubbling nostalgia, hoping to relive some of the comforting naiveté of her youth; other times she awaits the mail, knowing it will bring some book, some magazine, some tape she has forever been aware of but never quite had the nerve to ingest. The looming disappointment never disappoints.

At third blush, this is a deft and, with every passing chapter, increasingly fierce critique of evangelical ideology, but still a profoundly careful and ultimately respectful one. The nine chapters survey a kaleidoscope of facets in that ideology: music, scripture, film, sexual mores, foreign policy, cosmology, economics, humour and, inevitably (of course), apocalyptic.

Indeed, Jesusland circles and circles, delightfully, but must and does end at The End: not just the Book of Revelation from the Christian Bible, but also Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins’ Left Behind series of books as well. In a manner that epitomizes the enterprise and procedure of the whole work, in the final chapter Kidd tackles the one thing she has mostly avoided for the longest time: the Apocalypse. Again, the lonely voyage is one of dismay, despondency and despair. Somehow, though, Kidd surfaces — sadder, to be sure, but also wiser and, at long last, happier.

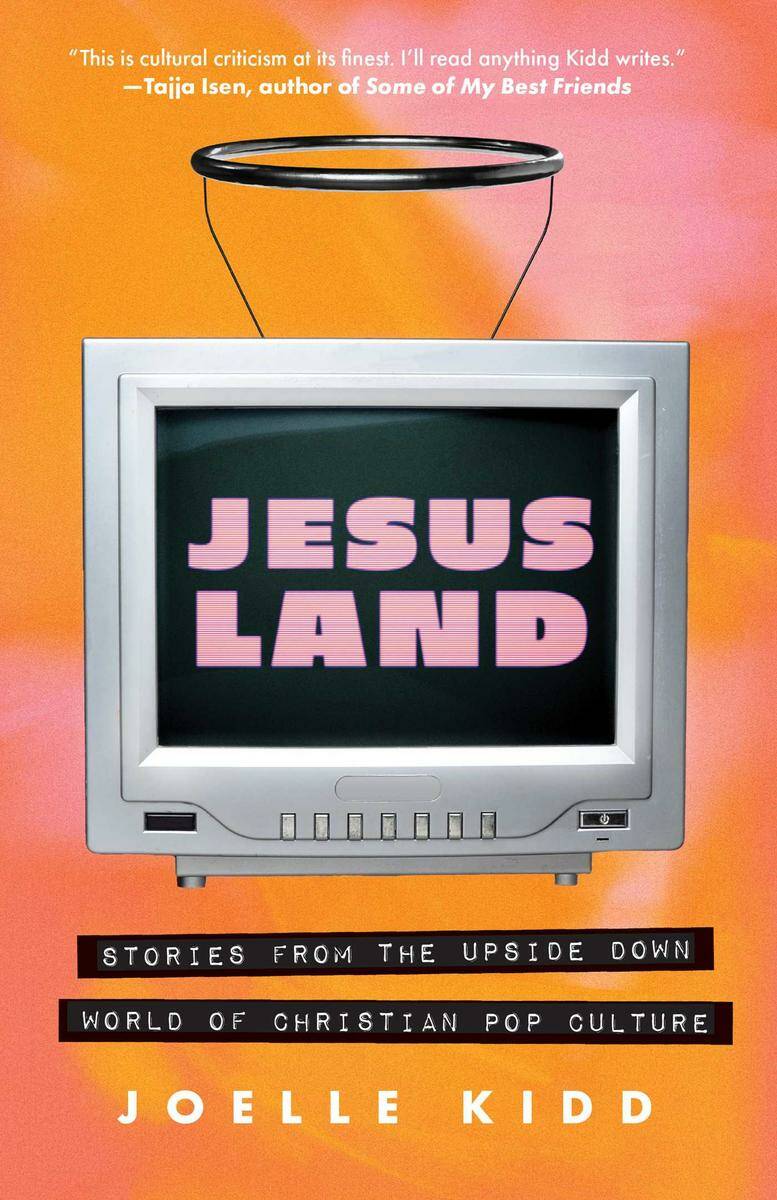

Jesusland

Jesusland is the work of an emerging writer — a true writer — already displaying the will and conviction to do the dirty work, the care to think systematically and exhaustively about the cumbersome data, the modesty not just to gander without but also to peer within and the verve to whip it all into a whole built on prose that flows, darts, returns and comes to apt rests again and again.

Although Jesusland in a sense hits the lottery with its timing, it is at its core a book overtly about a single decade of the past, about contemplating autobiography, about earnest inquiry, about seeking and finding contentment. It therefore is timely, yes, but quite unlikely to be locked in time.

Laurence Broadhurst teaches English and religion at St. Paul’s High School in Winnipeg.

Joelle Kidd launches Jesusland at McNally Robinson Booksellers’ Grant Park location on Friday at 7 p.m., where she’ll be joined in conversation by Andrew Unger.