Home to history Seven Oaks House Museum, Winnipeg's oldest home, tells the story of a family and Manitoba in the 19th century

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/05/2021 (1739 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Writer Brenda Suderman and photographer Mike Deal continue to share stories and photos from inside the vaults and hidden corners of the city’s community-run museums. Recently they visited Seven Oaks House Museum at 50 Mac St., located midway between Main and Scotia Streets in West Kildonan. Considered the oldest house in Winnipeg, the property was completed in 1853 for John and Mary Inkster and their children. The nine-room Georgian style house, known for its large porches, cedar-shingled roof and symmetrical appearance, housed family members until the death of daughter Mary in 1912, who willed the large property to the City of Winnipeg. The museum operates on donations and a grant from the City of Winnipeg, which also maintains the surrounding green space.

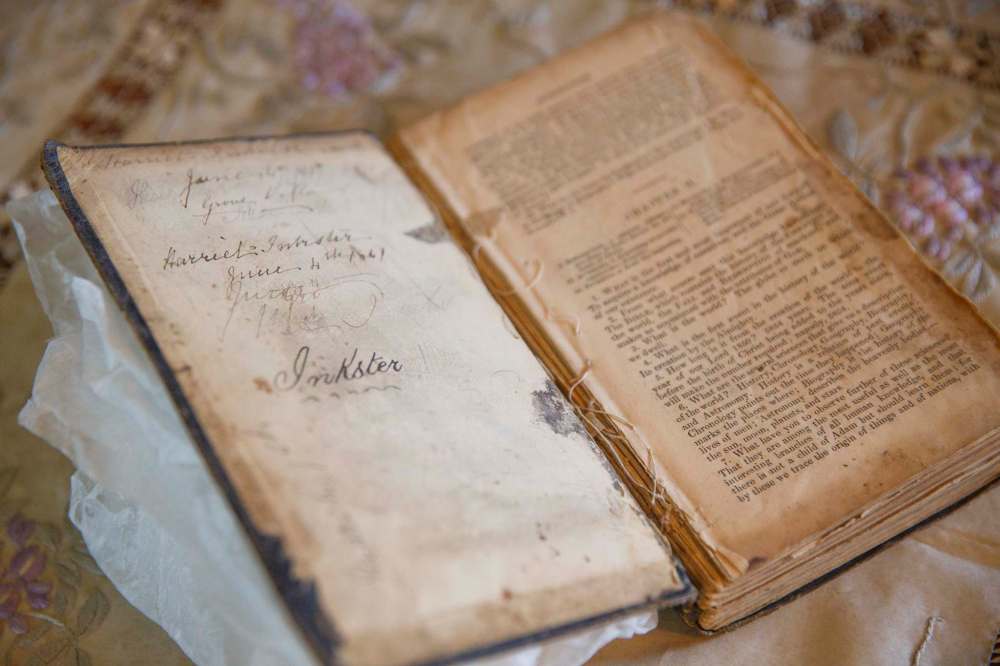

Hidden in plain sight for decades, a chance discovery inside a book at the city’s oldest house provides some tiny and illustrative details about 19th-century life at Seven Oaks House.

Last summer, a seasonal employee at the community-run museum was examining a theological book stored on the museum’s bookcase when she found tiny flowers pressed between the pages, probably by Harriet Inkster McMurray, daughter of the family who built the house 160 years ago.

“As we were leafing through the book, we found little pieces of embroidery thread and dried flowers that were squished between the pages of the book,” explained Eric Napier Strong, curator and manager of Seven Oaks House Museum.

One of nine children of John and Mary Sinclair Inkster, Harriet attended a private girls’ school for daughters of the Selkirk settlers, where she was instructed in subjects such as music, drawing, and needlework. (The northern Alberta community of Fort McMurray was named after her husband William, a factor with the Hudson’s Bay Company.)

Because of their delicate nature, those tiny fragments of what is likely her homework won’t ever be on display in the stately two-storey Georgian-style house, said Strong, but they do provide context for some other artifacts.

Usually open from the May long weekend to Labour Day, the museum is currently closed due to provincial health orders.

During their first pandemic summer, Strong and two seasonal staff prepared window displays on the main floor windows so visitors could see artifacts from the exterior, and also offered walking tours of the three-acre property, now run as a park by the City of Winnipeg.

“As soon as it is possible to open, we will have people inside,” said Strong about plans for 2021.

Home to about 3,000 artifacts, some belonging to the Inkster family and others collected to represent the time period of the house, the museum is more than a collection of items. Each room is furnished to a different period, starting with the family’s original 1820s era log cabin at the north end, repurposed to serve as the kitchen for the big house.

“People often forget that the house itself is the biggest artifact and it’s the most important one and the hardest to take care of,” Strong said, referring to the historically accurate paint and plaster finishes required to maintain the integrity of the provincial heritage site.

Once inside, visitors can admire the 19th-century parlour, furnished with an imported piano, several chairs or lounges and a unique if uncomfortable looking buffalo horn chair sporting nine pairs of horns in graduated sizes. Walls are decorated with a variety of artwork, some likely made by the Inkster family or close relatives.

Two framed wreaths of dried maple leaves and flowers, as well as black silk embroidered pillows lining the couch, date back to the same era as the tiny petals pressed inside Harriet’s book, said Strong.

Embroidery patterns taught to Harriet and other 19th-century girls in the Red River Colony probably later translated into beadwork designs, said Strong of the connection between settler and Indigenous handwork.

“They took these new designs and that’s what created beadwork (designs),” he said.

Those little details on the inside of the stately river-facing nine-room home, constructed from square-hewn logs, and featuring porches on three sides, speak to a more nuanced story of its earliest residents, said Strong.

“This house used to be presented as a white person’s house and Métis and Indigenous history was not talked about,” he said, referring to the family history of matriarch Mary Sinclair Inkster.

She was born in Oxford House in 1804 to Hudson Bay Company trader William Sinclair and Nahoway (baptized Margaret Sinclair), a woman of Métis and Swampy Cree ancestry.

Mary married John Inkster in 1826, two years after moving to the Red River Settlement, and the couple built a log cabin on the west side of the Red River. John Inkster, nicknamed Orkney Johnny, received a large land grant of 291 acres from HBC in 1835. The family moved into Seven Oaks House in 1853, splitting their previous log cabin into a kitchen for their new house and a general store/post office building, now located just south of the house.

Strong speculates Mary Inkster likely taught her daughters some traditional quillwork and beadwork and also encouraged their artistic pursuits.

“At home, the women carry on the family tradition,” he said, referring to floral patterns embroidered or beaded on everyday objects, including a watch pocket embroidered in silk on caribou hides.

Son Colin Inkster literally carried that tradition as well, in the form of an embroidered caribou hide tobacco pouch trimmed with silk velvet and marked with his initials.

“You get the idea he wasn’t ashamed of his heritage,” said Strong of the longtime sheriff and founding member of the Manitoba Historical Society.

“He carried an embroidered tobacco pouch every day of his life.”

Patriarch John Inkster left his mark on the house, employing his masonry skills learned in his native Orkney Islands to lay the stone foundation for the big house and building furnishings for it. The museum features four of his pieces: an armchair, day bed, an oak-framed upholstered sofa originally stuffed with horsehair and now in the process of being restored, and a tall breakfront for the dining room. Measuring 162 centimetres tall, Inkster built the piece from locally milled aspen and spruce and stained it to look like rosewood.

“That is the interesting part of this house,” explained Strong.

“We have the beadwork, we have the art the women in the family made, and we have the woodwork,”

Today’s visitors may not be surprised to see a couch inside such a large and luxurious house, but that piece of furniture speaks to the family’s wealth and status during the early days of European settlement in what is now Manitoba, said Strong.

“The idea of having leisure time with your family is not common,” Strong said of what is considered to be the oldest couch in Manitoba.

“So it would only have been wealthy families who had something like that.”

Despite those pieces, Strong intends Seven Oaks House Museum to stand as more than a monument to a wealthy Scottish-born businessman, who originally signed on as a labourer for Hudson’s Bay Company and went on to run a freight business, flour mill and general store. He would like the home to tell the story of Mary Sinclair Inkster and her children and the early days of what would become the City of Winnipeg.

“For me, it’s really important to celebrate the whole story,” he said of telling both the Indigenous and settler aspects to the family history.

“It’s not one or the other but making up for lost time and celebrating both.”

A recent archeological dig uncovered more of the Indigenous history, revealing decorated pre-contact Indigenous artifacts and discarded bison bones near a large tree in the front yard.

That discovery adds another chapter to the story of Seven Oaks House, named for a nearby creek and a stand of long-gone oak trees, and near the site of an 1816 battle between two rival fur trading companies. Now located within a public green space for Winnipeg residents, the house is more than a museum piece, but a living part of the city’s streetscape, said Strong.

“In a lot of ways, that is the history of Manitoba, that is the history of the city and it’s all right here in this place.”

brenda@suderman.com

Brenda Suderman has been a columnist in the Saturday paper since 2000, first writing about family entertainment, and about faith and religion since 2006.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.