Bigotry in our blood Winnipeg's tumultuous history reveals a city developed amid intolerant, xenophobic attitudes and behaviour continuing to affect life in 2020

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/10/2020 (1955 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The steeple’s cross-tipped spire stabbed the sky, rising high above the domed architecture of old St. Boniface College like the outstretched fingers of the faithful grasping for heaven.

The flames worked quickly, their appetite for destruction insatiable as they licked their way up walls and down halls, shattered stained-glass windows and sucked up oxygen like kindling until the small blaze transmogrified into an inferno.

It was 2:30 a.m. on Nov. 25, 1922.

A Jesuit brother awoke in a flash, startled by what he thought was the sound of an explosion. Instead, he found a fire ripping through the oldest post-secondary institution in Western Canada, which had stood on the grounds of Winnipeg’s Provencher Park since 1880.

Frantic, he rang a handbell, hoping the sound echoing through the darkness would wake the sleeping students and staff so they could escape.

Soon, it was all on fire, absolutely all of it, a glowing conflagration of orange and yellow and red that burned the cross-tipped spire like a matchstick set against the night.

Within hours, the building was gone, reduced to smouldering ruins, and 10 souls — nine of them children — had perished. It is, quite possibly, the deadliest fire in the city’s history.

The cause of the calamity remained unclear, and soon enough, rumours of arson began to spread — aided, in part, by media speculations, such as a Nov. 30 New York Times brief quoting an area woman who’d seen a “strange man… loitering around the grounds” on the eve of the fire.

At the time, Canadian Catholic institutions, particularly in Quebec, were falling to flames in shocking succession, one after another, like dominoes. In some cases, threatening letters signed by the Ku Klux Klan — then in its embryonic form in Canada and known for its anti-Catholic bigotry — were reportedly sent to churches before they burned.

Given that, and the violence unleashed by the group south of the border, it was only a matter of time before Winnipeggers wondered if what, at first, seemed a horrific and senseless tragedy was, in fact, a murderous crime.

It was probably inevitable someone posed the question aloud: Could the KKK have burned St. Boniface College to the ground?

● ● ●

At times it has felt as though 2020 has been a decade rolled into a single year.

In late May, Michelle Goldberg of the New York Times noted that 2020 began like 1974 (impeachment crisis), became 1918 (global pandemic), transformed into 1929 (economic crash), before erupting into 1968 (urban unrest).

56 per cent of Manitobans admit to past racist behaviour: poll

Posted:

More than half Manitobans admit to doing something in the past they now realize was racist, according to a recent survey, while a majority of those polled believe racism continues to be a serious problem in the province.

It has been a year defined by incendiary politics to the south, a once-in-a-century pandemic that’s claimed more than one million lives worldwide, unprecedented and disruptive lockdowns, economic disaster, chaos in the streets and a seemingly never-ending stream of racially charged incidents.

From George Floyd gasping for breath under a Minneapolis police officer’s knee in May, to Joyce Echaquan, an Indigenous woman, being subjected to racist remarks as she lay dying in a Quebec hospital bed last week, society has been forced to take a long, hard look in the mirror.

Closer to home, more than half of Manitobans — when asked during a recent Probe poll commissioned by the Free Press — admitted to saying or doing something racist in the past, and one-quarter of respondents said they’d personally experienced racism during the previous 12 months.

That, alone, is enough to show how pernicious and pervasive the problem of racism continues to be in Canadian society. And if you ask Manitobans, seven in 10 will agree, saying racism remains a “serious” concern in the province.

To better understand the ways in which racism has, and continues to, impact our community, the Free Press has been casting a critical eye on racial dynamics in Manitoba — historically, and currently.

● ● ●

In 1920, just 50 years after the province was born, Winnipeg was struggling. The economic boom in the early 1900s that flooded the provincial capital with money and people was over, dropping the city into a decline that would take decades to emerge from.

That year, the Indian Act made residential schools mandatory, and construction of the current Legislative Building was finished under a cloud of controversy caused by political corruption and kickbacks.

One year prior, Winnipeg gained clean running water when the aqueduct linking Shoal Lake First Nation and the city was completed in an act of colonialism that still resonates today, and had disastrous, long-lasting repercussions for the Indigenous community.

Though over, the battle camps drawn during the fractious Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 had fallen upon ethnic lines, with the Committee of 1,000 Citizens — comprised of the city’s WASP elite of bankers and business leaders — dismissing demands for better labour conditions from the “alien scum” working class.

And it was against this backdrop of colonialism, racism and ethnic hostility that organizers with the KKK — the terroristic hate group born in the American south — strode into Winnipeg in the 1920s to plot the Klan takeover of the city.

● ● ●

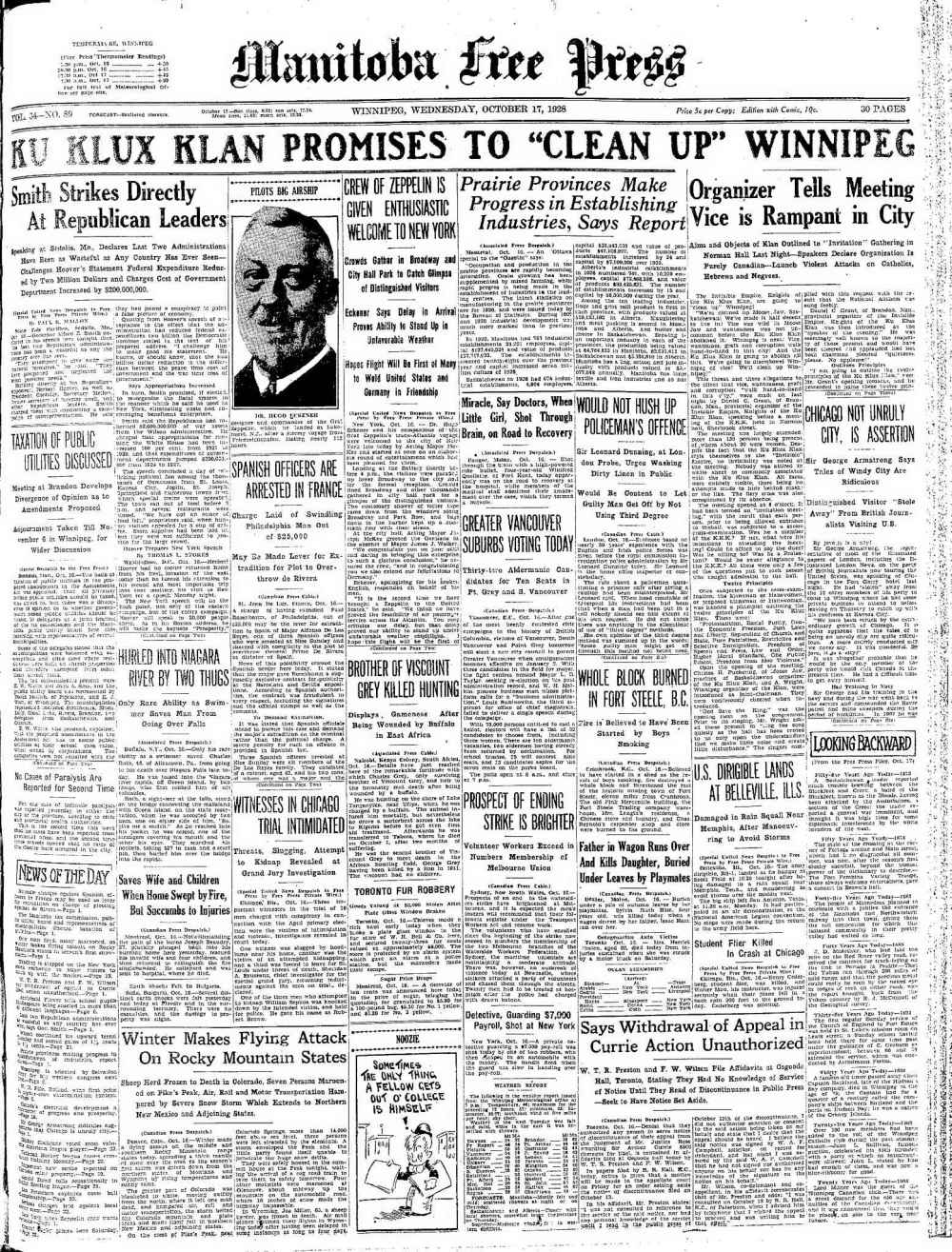

On June 1, 1928, a Canadian KKK organizer named Daniel Carlyle Grant held a meeting at the Royal Templars Hall on Young Street, hoping to galvanize white Protestants to his cause and establish a foothold for the organization in Winnipeg.

A tramway brakeman by profession, who was nicknamed “spark plug” by friends, Grant had cut his teeth in Klan organizing in Saskatchewan, where the “Invisible Empire” had a membership in the 1920s that numbered in the tens of thousands.

The rapid success of the Klan on the Canadian Prairies mirrored the resurgence of the organization in the U.S., which saw the hate group refounded in 1915, growing a membership of as many as four million people (15 per cent of the eligible population) by 1924.

The results were disastrous for Black Americans: a ruthless campaign of lynching and terror, particularly in the American South, where Klan members held influential roles in many communities, including political and law-enforcement offices.

On that June night in Winnipeg, Grant stood before a crowd as a torrent of vile abuse spewed forth from his lips, first against Papists, and what he deemed the sinister influence of the Roman Catholic Church in Canada, and then against Jews, whom he blood libelled as murderers of the son of God.

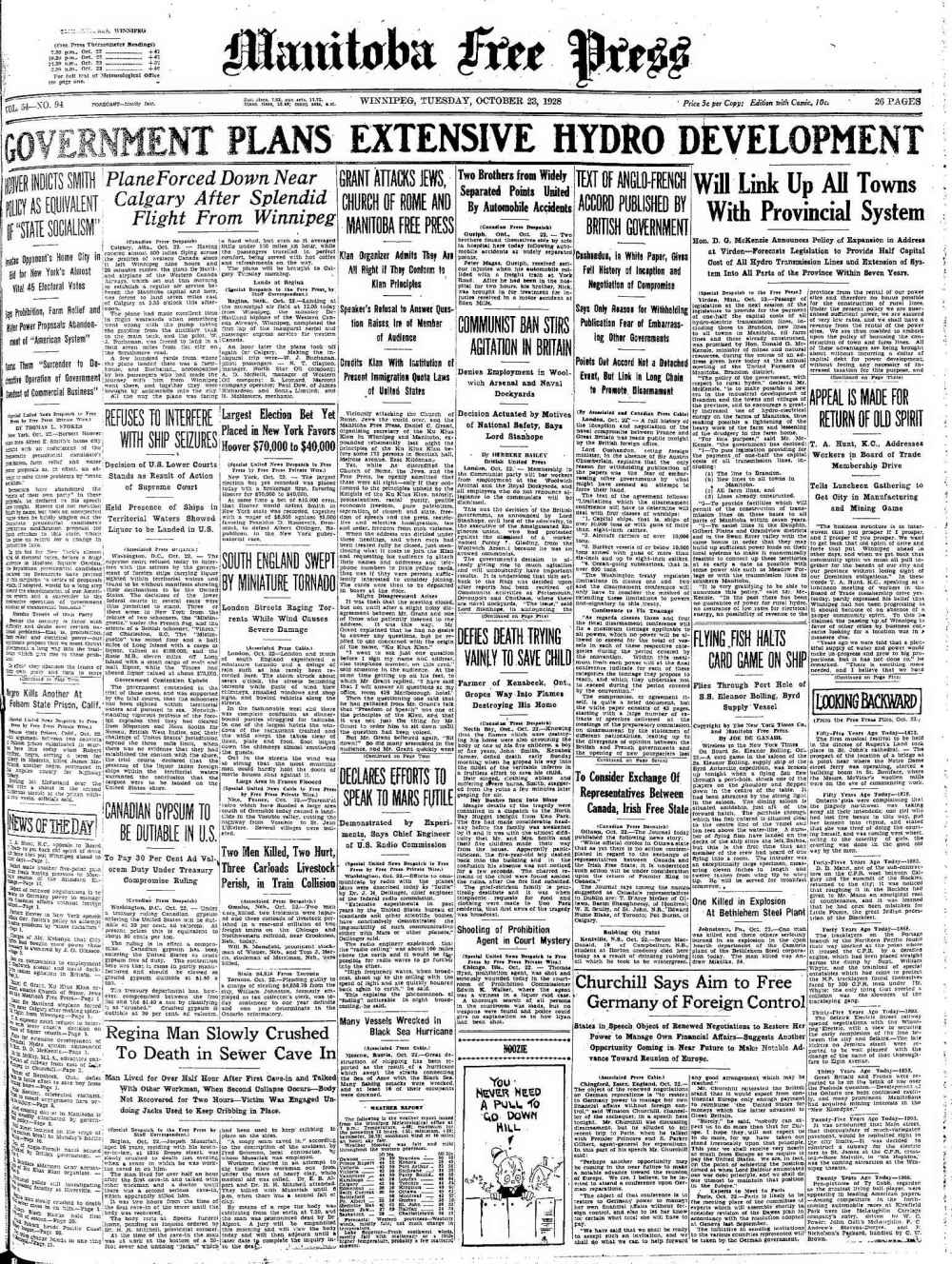

According to the historian Anthony Waldman, in an article published in Manitoba History in 2017, this was just the first of many Klan gatherings in Winnipeg in 1928.

Following a brief trip to Saskatchewan and a pit stop in Brandon, Grant returned to the city that autumn to recruit Winnipeggers into the secret society at $13 a pop —prompting a Free Press editorial to dub members “$13 suckers.”

On Oct. 16, a KKK rally at the Norman Dance Hall on Sherbrook Street drew a crowd of 150. Grant declared the Klan’s intention to “disembowel Winnipeg of vice” by fighting for “racial purity” and against Jews and the “scum of Papist Europe.”

Following the meeting, he told a reporter that Winnipeg’s chief of police and morality inspector both needed to be drummed out of office for dereliction of duty, and announced plans to soon hold more Klan rallies in the city.

True to his word, Grant organized a meeting several days later at the Berry Hall in St. Boniface, an area of the city with a significant Catholic presence, followed by another on Oct. 22 in East Kildonan.

At the latter meeting, Grant showed off his oratorial chops by promising, before an audience of 175 people, that the Klan would wage war against “every criminal, gambler, thug, libertine, girl miner, home wrecker, wife beater, dope peddler, moonshiner, crooked politician, shyster lawyer, white slaver (and) brothel madam.”

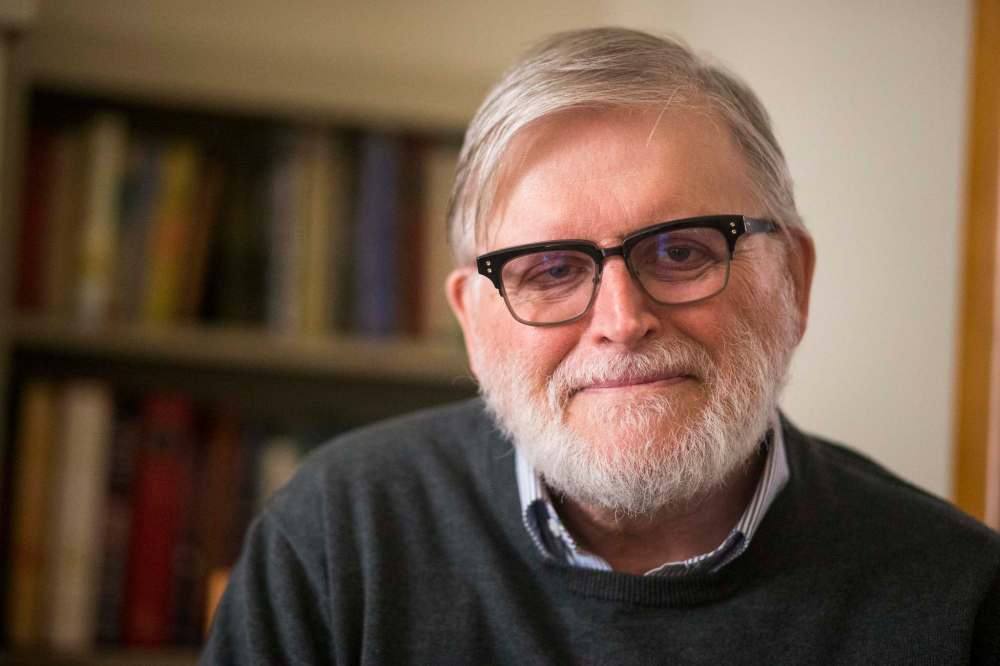

Allan Bartley, author of The KKK in Canada: A Century of Promoting Racism and Hate in the Peaceable Kingdom, says Grant was one of several of Klan organizers sent to Winnipeg in the 1920s to establish a Klavern — the term used to refer to local chapters.

“He was peddling the usual Klan message of anti-Jewish, anti-Catholic, anti-Papist, anti-Black, anti-Asian bigotry. He was quite blunt about it all. His message was, ‘We’re going to clean up Winnipeg,’” Bartley says.

“The police, the Catholic Church, the civic leaders generally, came down on him pretty hard. It didn’t go that well for him…. He had about two, three weeks of fame in Winnipeg before he wandered off into some of the smaller towns in Manitoba.”

While KKK organizers were ultimately unable to get a significant Klavern off the ground in Winnipeg in the 1920s, rural Manitobans proved more receptive to their message of hate.

The province had five Klaverns represented at a 1929 KKK convention in Saskatoon — although, given the secretive nature of the organization, it’s difficult to say where the chapters were located.

●●●

It’s somewhat surprising the KKK proved incapable of establishing a foothold in the city, given the success the group had found in neighbouring Saskatchewan, and what Waldman characterized as “fertile ground for the Klan to flourish.”

That included a “large French-speaking Catholic population, a Jewish community that exceeded 15,000, and large communities of Eastern European immigrants.” But during the same decade the Klan faltered in Winnipeg, racial and ethnic divisions were being stoked in other ways.

According to Jim Blanchard, a retired librarian who has written four books on Winnipeg history, the period following the First World War was destabilizing for the city. This was caused, in part, by large numbers of returning veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder who were unable to find work during the postwar economic downturn.

“When they came home they found that a lot of jobs they might have been able to do, particularly labouring jobs, were being done by the so-called enemy aliens, which would have been the Ukrainians, a few Germans, lots of people who got called Austrians,” Blanchard says.

“Nobody really knew anything about these people, and there was a lot of bad feeling towards Eastern Europeans at that time…. They thought of this as a British country, and here these people were interfering.”

Meanwhile, a wave of Communist and anti-colonial uprisings was sweeping the globe, which led to increased suspicion and animosity toward certain immigrant populations that were seen as harbouring radical sympathies and revolutionary ambitions.

For many in power, these suspicions were seemingly confirmed by the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, which led to a “red scare” — lesser known than its U.S. counterpart — Blanchard says.

“The red scare started in the United States, but it was here too. People were sent to jail for things they said, because they would have too much to drink and say something in a bar or a restaurant, and so they were put in jail for a while.” – Jim Blanchard

“The red scare started in the United States, but it was here too. People were sent to jail for things they said, because they would have too much to drink and say something in a bar or a restaurant, and so they were put in jail for a while,” he says.

“The idea was, ‘The enemy isn’t the Germans anymore— they’re beat. The enemy is the Communists.’ There was a lot of crazy nervousness about that, this idea that Winnipeg could go red.”

Winnipeg was also dealing with issues of segregation — both formally and informally. Clustered in the North End, where they were cleaved off from the rest of the city by the rail lines, were large numbers of Jews, Ukrainians and other Eastern European immigrants.

Robert Vineberg, a research fellow at the Canada West Foundation and former director general of Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s Prairies and Northern Territories region, says there was often openly expressed hostility towards these communities.

“You can find references in the newspapers to what was called ‘inferior races,’ and these were the Poles, the Ukrainians, southern Italians, Greeks and so on. Basically, there was very little immigration from elsewhere,” Vineberg says.

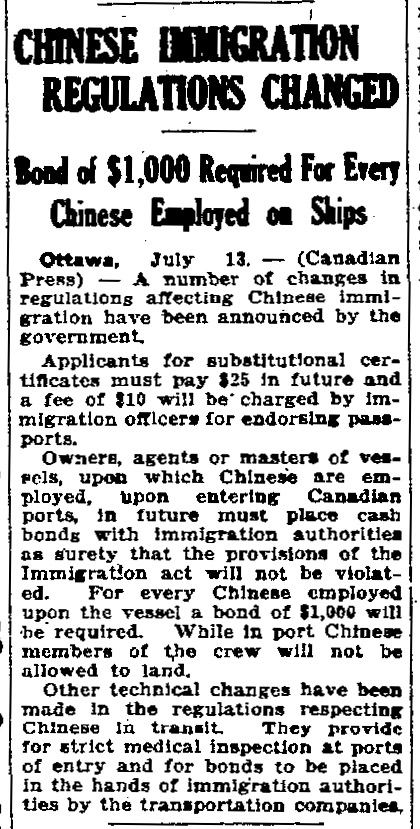

In 1923, Parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act, a racist policy that almost entirely banned immigration by Chinese nationals or individuals of Chinese descent.

“It basically prevented any immigration from China and that was only repealed in 1947, so that’s a specific example of institutionalized racism,” Vineberg says.

At the same time, Indigenous peoples were being pushed out of the city, as Winnipeggers in positions of power and influence went about a project aimed at making the community as white as possible, says Adele Perry, a historian and associate professor at the University of Manitoba.

“Indigenous people were being sent the message that Winnipeg was not a space for them,” Perry says.

“It’s about colonialism and land and power, but those things are abetted and given strength daily by ideas and languages of racism, by ways of seeing racialized people — including Indigenous people — as separate and lesser.”

A wide range of informal “cultural and social practices” kept Indigenous peoples separate from non-Indigenous (particularly white) people, Perry says, while the 1927 amendment to the Indian Act further entrenched segregation.

Known as Section 141, the amendment followed an uptick in Indigenous political organizing that led to land claims being filed against Ottawa. The amendment barred First Nations, on punishment of imprisonment, of retaining lawyers to file such claims.

A mixture of cultural norms and practices on the one hand, with forms of state-directed oppression on the other, led to drastic changes in the city’s demographics.

In 1870, Winnipeg was an “overwhelmingly Indigenous place,” but over the coming decades it’s purposefully purged of Indigenous elements, until it becomes an “overwhelmingly non-Indigenous” community by the early 20th century, Perry says.

“For most of the 19th and 20th century, Canada has a sort of racism that is just in the water and is not viewed as something that shouldn’t be spoken of. It’s very out in the open,” she says.

“And all the statistics that people are familiar with about the over-incarceration of Indigenous people, the radical over-representation of Indigenous children in child welfare, questions of Indigenous people and policing, those are the legacies of that world.” – Adele Perry

“And all the statistics that people are familiar with about the over-incarceration of Indigenous people, the radical over-representation of Indigenous children in child welfare, questions of Indigenous people and policing, those are the legacies of that world.”

Sadly, the divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities is a problem that has echoed down through history. During recent polling, eight in 10 Manitobans said the “division between Indigenous and non-Indigenous citizens is a serious issue in our province” — a finding that has “remained relatively consistent” in recent years.

This should not come as a surprise, given the well-established state of affairs alluded to by Perry, and the lives of those — such as Brian Sinclair or Tina Fontaine or Matthew Dumas, among countless others — whose names have been etched into our collective DNA.

The weight and horror of it all sits like an open scar on Manitoba’s heart.

●●●

Fears among Winnipeggers the KKK was responsible for the fatal 1922 fire at St. Boniface College are likely unfounded, according to Bartley, who spent a significant amount of time researching the wave of blazes at Catholic institutions in Canada in the 1920s.

The most likely explanation for the rash of fires is that church authorities had allowed the “maintenance and care of a lot of these facilities to fall into very bad state,” Bartley says, adding that a lot were “the result of negligence” and “decrepit” buildings.

“These factors, in my mind, probably mitigate against the Klan being the source of the fires, but that doesn’t take away from the fact the Klan generated a climate of violence in Canada,” Bartley says.

“It’s just that in this case, I don’t think you can lay blame at the feet of the Klan — not without more evidence.”

“These factors, in my mind, probably mitigate against the Klan being the source of the fires, but that doesn’t take away from the fact the Klan generated a climate of violence in Canada.” – Allan Bartley

On Feb. 7, 1923, provincial fire commissioner Charles Heath released a report, based on the testimony of 69 witnesses, suggesting careless smoking in the boys washroom sparked the blaze. Nevertheless, rumours of Klan involvement persisted and linger to this day.

Given the climate of the time, which included multiple violent episodes associated with the KKK in Canada, Bartley says he’s not surprised some Winnipeggers suspected the Klan was behind the fire.

“The Klan in the 1920s in the United States was extremely violent, particularly in the southern United States. That was a reputation that travelled across the continent…. So the level of concern some Canadians had was quite understandable. I think it was a valid concern,” he says.

The history of the KKK in Canada, particularly the success it found in the Prairies in the 1920s, says something profound about the deep roots racism has in the country, according to Bartley.

“I came, reluctantly, to conclude there is a strain of racism and hatred in Canadian society that runs quite deep and has been present for a very long time. The Klan managed to tap into that, albeit briefly,” Bartley says.

“We still have it today. It waxes and it wanes. It was present then and it is present now. It has been present throughout our history. I think we, as a society, have to be very mindful of that, not just in regard to the past, but also currently, and going forward into the future.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

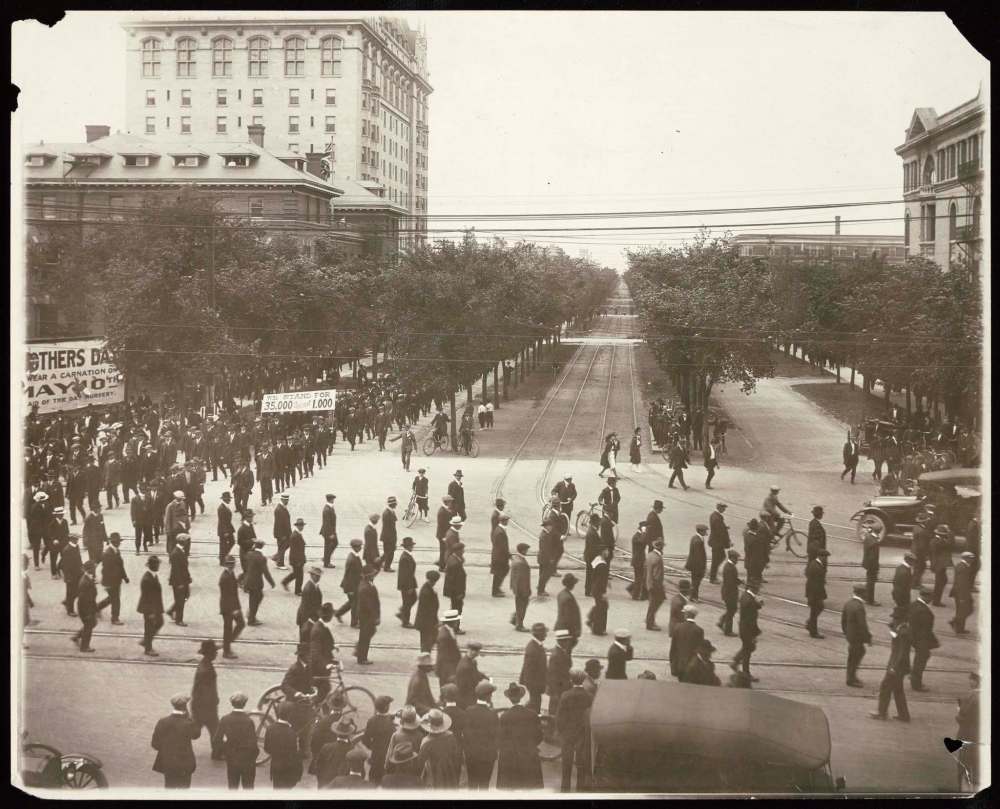

![WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ARCHIVES

On Wednesday, June 4, 1919 In front of the government Building Norris, with policeman, to the left of the [illegible] Loyal Returned Soldiers](https://staging.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/NEP8820082.jpg?w=1000)

![WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ARCHIVES

On Wednesday, June 4, 191 9In front of the government Building Norris, with policeman, to the left of the [illegible]Loyal Returned Soldiers](https://staging.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/NEP8820081.jpg?w=1000)

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.